Emmett Dieleman’s troubles started on Day 3, when his 7-pound body proved too weak to pass the car seat test that would allow him to go home from the hospital.

From there, his problems snowballed.

First, he had blood in his stool. Then doctors found his platelet count to be low.

After two weeks of intensive care at a local hospital with no improvement and no clear diagnosis, he moved to the NICU in the Gerber Foundation Neonatal Center at Spectrum Health Helen DeVos Children’s Hospital.

Over time, more symptoms sprang up.

Vomiting. Diarrhea. Ulcers in the mouth. And, eventually, ulcerations throughout his digestive tract.

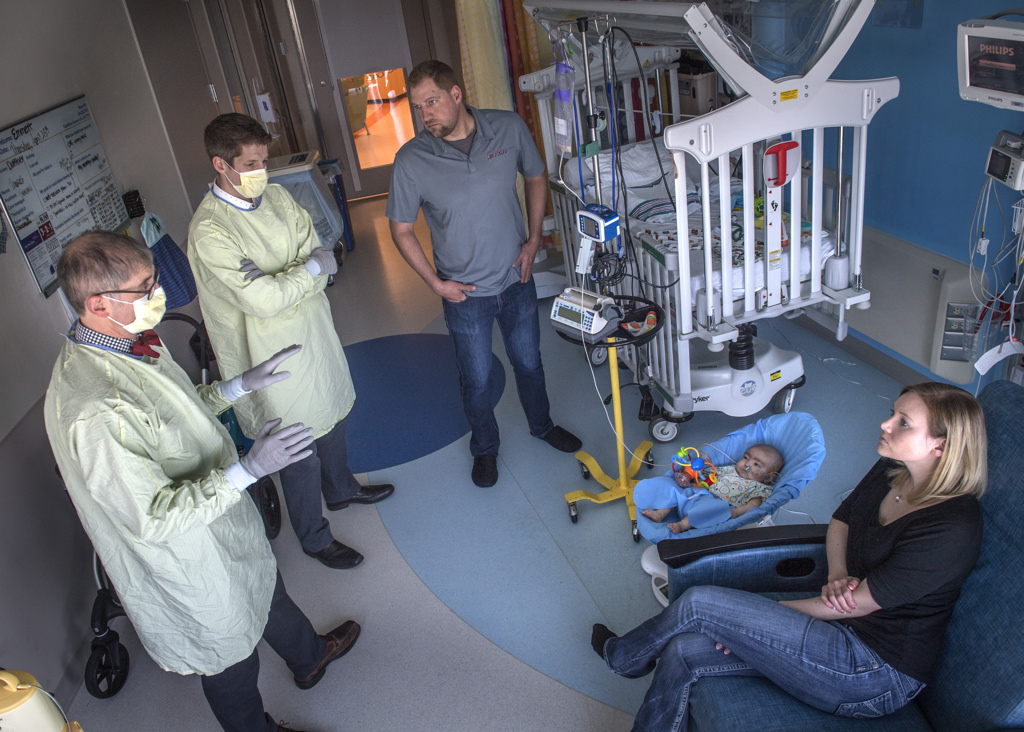

Pediatric specialists got involved in his care—first hematology, then gastroenterology, immunology, dermatology and infectious disease.

Several symptoms pointed to inflammatory bowel disease—a rare illness in infants and children—but that diagnosis didn’t tell the whole story.

“He started having a lot of problems adding up that there wasn’t a unifying diagnosis for,” said Nicholas Hartog, MD, an allergy and immunology specialist with the Spectrum Health immunodeficiency clinic. “Just more and more clues that there was something more going on.”

Genetic testing

From the first time he met Emmett, Dr. Hartog suspected a problem with his immune system, probably a genetic issue. Though he still had to rule out a handful of other disorders, he quickly brought in the genetics team to discuss genetic testing.

When the other results came back normal, the doctors agreed whole exome sequencing would be the best route to an answer.

“It’s looking for a genetic disease,” Dr. Hartog said. “It literally looks at every gene in your body that codes for a protein and says, ‘Can we find any gene that describes the problem?’”

By this time Emmett had reached 10 weeks old. His parents, Heather VanAller and Kevin Dieleman, of Alto, Michigan, had grown weary of watching their baby suffer while they waited for a remedy.

“It was hard feeling helpless, because we knew he was in so much pain,” VanAller said.

“And the diagnoses (the doctors) brought up, they kept saying the same thing—‘It sounds like this,’ but then there was always one thing that didn’t match, and then that didn’t make sense. It was just very hard to hear over and over again.”

Even before the genetic testing results came back, Dr. Hartog gave his colleagues in the pediatric bone marrow transplant program a heads-up: “I think I’ve got a patient for you.”

When Emmett turned 4 months old, the sequencing results came back from the genetic testing lab. Emmett had a protein deficiency so rare that he is only the 13th person in the world to be documented with it.

A deficit of this protein, called WDR1, can lead to life-threatening immune system problems and hyperinflammation—the source of Emmett’s ulcerated mouth and intestines.

The genetic test also revealed a second, less serious mutation that explained the eczema and skin rashes Emmett experienced.

Without whole exome sequencing, Emmett’s diagnosis would have remained a mystery, Dr. Hartog said.

Bone marrow transplant

By the time the answer came back, Emmett’s symptoms had turned dire: frequent vomiting, ulcerations throughout his system—even in his eyes—and difficulty putting on weight.

“He really started to decline,” Dr. Hartog said.

The only solution would be a bone marrow transplant—replacing his diseased bone marrow with healthy bone marrow stem cells.

Learning the source of Emmett’s illness gave her “instant relief,” VanAller said, but it also frightened her because the medical community knows so little about the WDR1 mutation.

Not to mention the fear she felt at the thought of putting her baby through the transplantation process. At the same time, Emmett’s parents knew it represented their best hope.

“Really, we had no choice because he was so bad,” VanAller said. Without it, “the outcome was not going to be pretty.”

So in December 2018, Emmett’s medical team put him on a fast track for bone marrow transplantation.

For Emmett’s nurses, this meant getting his weight up to 15 pounds while trying to keep him comfortable and infection free.

For his family, it meant one parent would stay at the hospital with Emmett, while the other tried to keep life at home as normal as possible for their daughter, Taylor, 9.

For the bone marrow transplant team, it involved searching the National Marrow Donor Program registry, narrowing the pool to find the best possible match, confirming the preferred donor’s willingness to participate, coordinating with the donor’s doctors to validate his medical health and setting a date for the donation and infusion.

“Getting the donor ready is a process that usually takes six to eight weeks, so the sooner you start the process, the shorter the time to transplant,” said Aly Abdel-Mageed, MD, section chief for the pediatric bone marrow transplant program at Helen DeVos Children’s Hospital.

By mid-January 2019, it was all systems go.

Emmett underwent chemotherapy treatments to wipe out his nonfunctional immune system in preparation for the transplant. His donor, an unrelated male who is a 90% match for Emmett’s tissue type, prepared to have his bone marrow removed at month’s end.

In the meantime, Emmett’s doctors consulted with colleagues in San Francisco, Maryland and London—the only places they could find that had used bone marrow transplantation to treat Emmett’s rare disorder or something similar.

“We worked closely with them to learn what they had done, what they wish they had done differently and to learn from the world’s experience—which is two people,” Dr. Hartog said. “Emmett is the third patient transplanted in the world, that we know of.”

The doctors’ insights helped Dr. Mageed and his partner, Ulrich Duffner, MD, customize their approach to Emmett’s transplant.

They did several things differently than they normally do, given Emmett’s small size, the nature of his disease and the donor situation. They believed he had an 80% chance of being cured.

“It is a very rare condition, (but) we went in hopeful based on our history of treating patients with multiple other conditions similar to his,” Dr. Mageed said.

On Jan. 31, Emmett received the donor cells. Then the watching and waiting began. Would the graft take?

Twelve days later, doctors saw the first positive signs. As time passed, they could confirm the new cells functioned well. The transplant had been a success.

“Right now, by all accounts, his immune disease seems cured, completely cured,” Dr. Hartog said after Emmett had passed the 6-months-post-transplant mark.

“The GI is all cleared up, his oral ulcers are gone, everything.”

Hurdles and hopes

Emmett faced some big hurdles in his first 100 days after transplant—complications in the form of kidney trouble, a complex form of anemia and a liver disorder called veno-occlusive disease, all of which caused fluid to build up in his abdominal cavity and around his heart.

Each of these problems, though threatening, turned out to be reversible, thanks to his team of doctors, which by now also included specialists in pediatric cardiology, nephrology and neurology.

“They’ve been smart from the beginning, they really have—they’ve been amazing,” VanAller said, noting that the team took precautions from the start, knowing a transplant could become necessary.

Today, the biggest concern is the risk of infection, since Emmett remains on immunosuppressant medication to reduce the risk of his body rejecting the transplant. The more time passes, the more likely he is to escape further complications.

“There usually is a milestone at 6 months and a milestone at 12 months post transplant,” Dr. Mageed said. “As time progresses, every day is a good day for him. Thank God he gets stronger every day.”

Even though Emmett is out of the hospital now, it’s going to take quite a while for things to feel normal at home, VanAller said.

The family is zealous about cleaning, handwashing and fending off germs. Only immediate family members are allowed inside the home.

Camping trips and other family adventures are on indefinite hold.

Twice a week, Emmett visits the hospital’s bone marrow transplant clinic for monitoring and blood tests. He follows up regularly with specialists in pediatric gastroenterology, nephrology and immunology to make sure everything still looks good.

To make up for lost time, Emmett also participates in outpatient physical, occupational and speech therapy.

“It’s kind of hard to think about the future because we pretty much still live day by day—dare I say week by week now?” VanAller said.

Yet, as she anticipated Emmett’s first birthday, she reflected with gratitude on his extraordinary progress.

“Oh, he is just a completely different baby,” she said. “He’s very happy, he sleeps through the night, he is for the most part just very content and easygoing. …

“It’s just amazing to see how far he’s come.”

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>