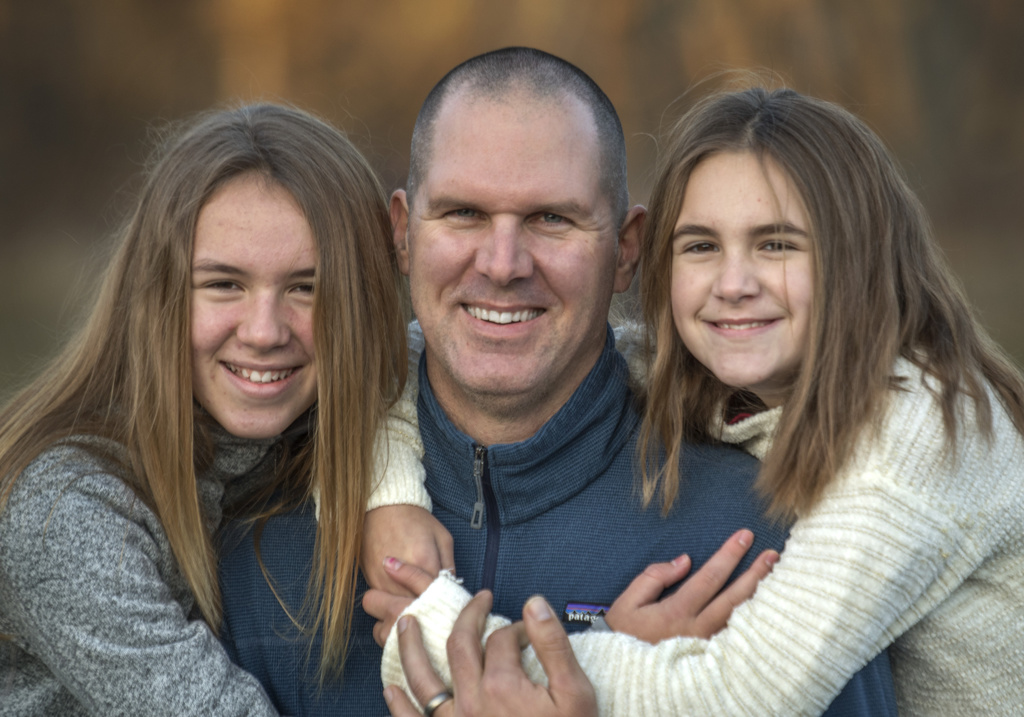

Ted Kushion is the kind of guy who has always been athletic. He trained for marathons. He biked. He coached. He even made his career in sports and sporting goods.

“I was working with athletes my whole life and had always been one,” Ted said.

The 39-year-old Lowell, Michigan, resident had no hint of a heart problem.

Until the weekend of Labor Day 2019. While watching a movie at home, he began coughing and gagging for no apparent reason.

He went to get water. His wife, Deb, followed.

“I thought he was sleepwalking, he wouldn’t respond,” Deb said. As Ted struggled to breathe, she helped him to the floor.

He had suffered sudden cardiac arrest.

Deb immediately started CPR, which she had learned as a teenage lifeguard. And she called 911.

By the time paramedics shocked him with an automated external defibrillator, or AED, Ted had been without a pulse for 20 minutes.

He arrived by ambulance to Spectrum Health Butterworth Hospital, where doctors connected him to a ventilator to keep him alive.

Deb, a physical therapist, prepared herself for the worst. She had been working with brain-injured patients for the previous 12 years.

“I saw what the recovery could be, good and bad, knowing how long he was down and what could have happened,” Deb said. “It was really scary there for a bit.”

When Ted came off the ventilator after three days, her worries intensified.

He appeared confused and unsteady on his feet.

As physical, occupational and speech therapy began, however, Ted’s mind cleared and his body grew stronger.

“It’s amazing. If his wife wasn’t with him, he probably would have died from this,” Spectrum Health cardiac electrophysiologist Michael Brunner, MD, said. “She saved his life and she kept the blood flowing to his brain.”

Electrical issues within the heart

The cause of Ted’s sudden cardiac arrest seemed a mystery at first.

Doctors checked him for a possible stroke, cardiac blockage and pulmonary embolism without finding an answer.

Genetic testing didn’t offer any insight, according to Dr. Brunner, who describes himself as an electrician for the heart. He thrives on solving medical puzzles.

After several EKGs, Dr. Brunner finally discovered the likely culprit: an extra nerve pathway connecting the top and bottom chambers of Ted’s heart.

An electrophysiology study of the heart confirmed his diagnosis.

“Our concern was the extra pathway put him at risk for having a very rapid heart rate,” Dr. Brunner said. “It was a super rare thing.”

They took Ted to Spectrum Health Hospitals Fred and Lena Meijer Heart Center, where Dr. Brunner performed a cardiac ablation to destroy the extra pathway.

Next he put an implantable cardiac defibrillator in Ted’s chest.

The defibrillator could be the lifesaver. If Ted’s heart goes into an abnormal rhythm, it will automatically shock the heart back into a normal heartbeat.

Road to recovery

As soon as Ted began feeling stronger, he got restless.

“I remember sitting in the hospital bed and asking about going back to work and what that looks like,” Ted said.

Doctors warned him it could take six months of rehabilitation before he would be ready.

“It was a pretty scary thing to hear, looking at financial security,” Ted said. “To say it was stressful would be an understatement.”

Deb had a different reaction.

“Holy cow. I watched you die,” she said. “You don’t need to go back to work yet.”

Everyone underestimated Ted’s determination.

Just two weeks after leaving the hospital, he headed out on his mountain bike, much to his wife’s dismay.

Less than two months later, Ted returned to work, traveling to specialty running stores across the Midwest. Despite his voice being temporarily reduced by the intubation, he performed his job.

“For me, it was a race to get back to normal as quickly as I could,” he said.

The following spring, at age 40, Ted began thinking like an athlete again.

“I wanted to have something to train for and have a goal,” he said.

When he found a 111-mile gravel bike race, he got the OK from Dr. Brunner to compete. He was pleasantly surprised to have enough stamina to complete the event.

The following weekend, he did a 65-mile virtual race. He’s been riding every weekend since.

When he works out he wears a heart monitor. He uses an app on his phone that lets Deb track his progress, which puts her mind at ease.

Deb doesn’t downplay the emotional and mental effect of Ted’s collapse. She struggled with PTSD afterward and found help through therapy.

Overall, both Kushions are filled with gratitude.

“Everyone has just been phenomenal,” Deb said. “I’m just so grateful to everyone from start to finish. Everything went right from the second Ted’s heart went wrong.”

Ted is determined to give back by helping others survive cardiac issues.

His story even inspired his employer, Mizuno USA—the company provided CPR training for all employees at its annual convention.

Ted is also raising money to place AEDs in the boutique running stores he serves across the Midwest, knowing stores often host races where the help can be miles away.

“If it weren’t for an AED, I would not be here today,” Ted said. “There’s no question.”

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

Awesome comeback story. Deb was in the right place at the right time. So fortunate she had the proper training to deal with this medical emergency. The defibrillator is such a great tool. Ted really worked hard to come back. So happy he is fully recovered.

Ted is our nephew and very dear to us. He and our older son were college roommate at GVSU. They are close hunting and fishing buddies still. We were devastated when we heard the news of Ted’s episode and thankful beyond measure at his recovery. So glad Deb was so skilled and also the efforts of the Spectrum team who saved his life.

We are so grateful and love Ted and his whole family so much,

I am glad this man got help for his heart rhythm problem; he is very fortunate. I have similar happen to me; sudden onset of strange heartbeat and can’t breathe or talk, come close to fainting. Have been to drs many times for this, but they can’t find the cause and won’t refer me to an EP dr. The anxiety of this takes over my life; I try to manage the fear of this happening by staying close to home and taking anti-anxiety med. I’ve given up on getting help for this.

Hi Sandra, I just sent you an email, encouraging you to reach out for a second opinion. Wishing you the absolute best, and answers to your lingering health concern. Best, Cheryl

Ted is my oldest and best friend, and Deb is a friend from high school. He was right there as one of my pace riders as I competed in my first adaptive (virtual) marathon in October of 2020, a year after his heart attack.. I was later told that Ted was riding with and for his hero. The truth is Ted is my hero!