When Maggie Campbell checked into the emergency department at a Kalamazoo, Michigan, hospital in 2018, she stood at 5 feet, 2 inches and weighed 98 pounds.

She had a pale coloring—a bit yellow—and felt weak and tired.

And she had by then grown weary of living like this.

Her friends thought she might have an eating disorder. She let them think as much.

She kept her secret mostly to herself, sharing it only with her husband and parents.

“My BMI back then was … super scary,” Campbell, of Portage, said. “But it wasn’t because I didn’t want to eat. It was because I couldn’t swallow.”

Campbell hadn’t been able to swallow with ease most of her life.

Sometimes food would come right back up before it ever reached her stomach. Sometimes it got stuck somewhere in her esophagus, causing her chest pain.

“Doctors just thought I had acid reflux as a kid,” Campbell said. “But by 2011 there were times that I took a drink and the liquid wouldn’t go down, came right back up. It was like a choking sensation. That went on for about six months.”

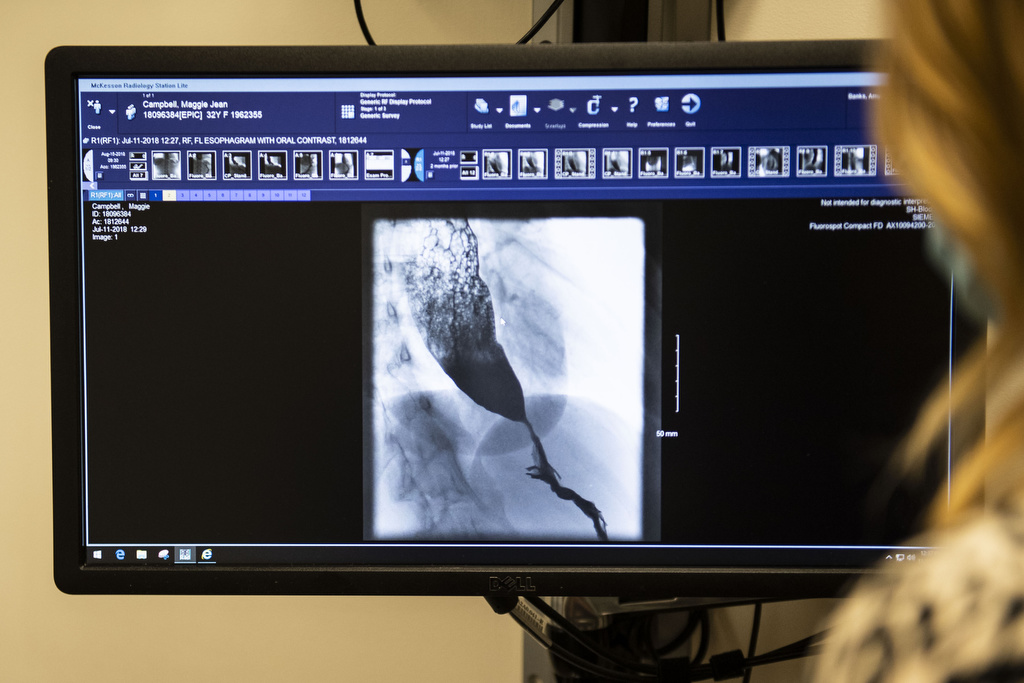

Early in 2012, Campbell went to see a gastroenterologist in Kalamazoo. She underwent a barium swallow test, an X-ray that can trace a liquid’s path through the upper gastrointestinal tract.

“He said he thought I had esophageal cancer and sent me immediately to the hospital,” Campbell recalled. “I was only 25 years old then and that was terrifying.”

But tests showed she didn’t have cancer.

Something else.

“I was finally given a diagnosis of achalasia,” she said.

Campbell went home and did her research.

Achalasia? She had never heard of it.

She would come to learn much about this rare disease.

A tearful arrival

Campbell, 34, can count herself among the 100,000 people worldwide with achalasia.

Achalasia means “failure to relax.”

According to The American Journal of Gastroenterology, there’s no known cause for the disease. It affects the esophagus, the tube connecting mouth to stomach.

At the bottom of the esophagus is a ring of muscle, a sphincter that closes off the esophagus from the stomach, allowing food to pass in and not back out.

A person with achalasia can experience a sort of paralysis of the esophagus. The muscles that should move food and liquids down toward the stomach no longer squeeze or contract properly.

Food remains in the esophagus rather than moving down into the stomach.

When Campbell went to the emergency department in 2018, she felt desperate for help.

“I had been told that nothing could be done,” Campbell said.

A doctor ordered a new barium swallow test. The test results again showed a severe case of achalasia.

Campbell’s condition had become critical. She would need surgery.

Her doctor connected her with Amy Banks-Venegoni, MD, at Spectrum Health Blodgett Hospital in Grand Rapids.

A confirmed diagnosis

Dr. Banks-Venegoni learned diet modification had been Campbell’s only course of treatment over the years.

“Maggie was tearful when she arrived in my office. She was frustrated and had little energy,” Dr. Banks-Venegoni said.

The doctor ordered an esophageal manometry test.

“A tube with sensors is inserted through the nose into the esophagus, down to the stomach, while the patient swallows 10 times so that we can observe any problems with movement or pressure,” Dr. Banks-Venegoni said.

Dr. Banks-Venegoni specializes in minimally invasive surgery, reflux surgery and esophageal dysmotility disorders at Spectrum Health.

The doctor confirmed the achalasia diagnosis, but added it had become particularly severe in Campbell’s case.

“The cause for achalasia is unknown, but there is a theory that it may be a respiratory virus,” she said. “We see it run in families, so there seems to also be a genetic predisposition.

“It’s often misdiagnosed as GERD or acid reflux.”

Doctors scheduled Campbell for an Aug. 14, 2018, surgery at Blodgett Hospital.

Finding relief

The surgery would require less than two hours.

Dr. Banks-Venegoni made five small incisions laparoscopically, each less than one inch in length and in the upper abdomen.

Then she cut the sphincter muscle, about seven to eight centimeters, from the stomach to high up into the chest, as high on the esophagus as possible.

To prevent reflux from the stomach into the esophagus, the surgeon wrapped the stomach around the esophagus in a process known as Dor fundoplication.

It creates a sort of low-pressure valve.

“I had a partial wrap,” Campbell said. “I was bawling after the surgery. I was so relieved. I made a video of the first time I drank a glass of water for another barium test after the surgery, to see if everything was working.”

She still watches the video at least once a week.

“I kept asking for more water, not because I was thirsty but because it was so wonderful to be able to swallow,” she said.

“It’s what I usually see after this kind of surgery,” Dr. Banks-Venegoni said. “People are so relieved.”

Campbell had to stay on a liquid diet for five days. She went back to solid food within two weeks.

“Swallowing with this disease is never normal because the esophagus is paralyzed, but now that the tight muscle is open, food and liquid goes through the esophagus much easier and that improves symptoms greatly,” the doctor said.

An achalasia warrior

These days, Campbell enjoys a broad range of foods.

“I can eat anything now, as long as it is in small pieces,” she said. “I have to drink water every three bites to wash food down. Otherwise it feels like a traffic jam in there.

“I still need water and gravity to move my food down to my stomach, but it’s all been worth it,” she said.

Campbell’s experience inspired her to start a private support group on Facebook, Achalasia Warriors. It now has nearly 500 members from around the world.

They share their stories and support each other with positive messages through challenging times.

Campbell plans to organize a fundraiser for achalasia research.

“There is no cure for achalasia, so that scares people,” she said. “People try to ignore it, like I did for so many years.

“But you come to a point where you want to talk about it, you want to get better,” she said.

Her surgery became the turning point.

“I want others to know about that,” she said. “And to offer hope.”

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

Maggie is an amazingly strong woman! The best part is she is sharing her experience and helping others along the way. I am grateful to know this awesome human and her wonderful family.

What a wonderful story of hope.

Your willingness to share will be a gift to so many!