Amid colorful banners, mylar balloons and the broad smiles of her parents and medical staff, Lilly Vanden Bosch watched as a registered nurse attached a small bag of reddish fluid to the IV pole beside her bed.

“It looks just like blood,” observed 10-year-old Lilly as she snuggled in her bed at Spectrum Health Helen DeVos Children’s Hospital with her mom, Meg Vanden Bosch, tucked by her side.

Blood. And so much more.

The bag contains blood stem cells and bone marrow, harvested from an overseas donor and transported by courier to Grand Rapids, Michigan, with the goal of annihilating the rare blood disorder Lilly has battled for nearly three years.

“This is pretty overwhelming,” her dad, Tom Vanden Bosch, said as the fluids dripped through an IV line and into Lilly’s body. “How do you adequately thank someone you have never met for giving of themselves to a stranger, for giving my daughter a shot at life?”

Finding a match

Lilly’s new bone marrow came to Grand Rapids courtesy of the National Marrow Donor Program, the largest marrow registry in the United States. The program has access to registries worldwide, including the ones in Europe where Lilly’s donor lives.

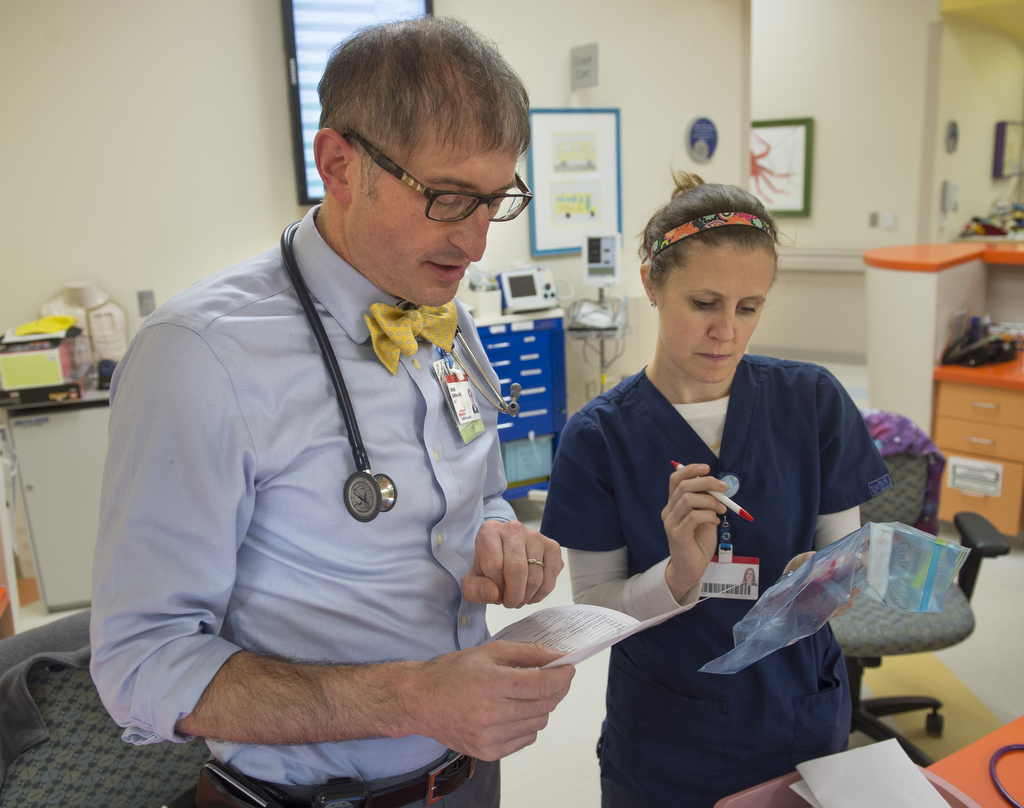

Because bone marrow matches are based largely on ethnicity, it is common for people in the U.S. to be matched with European donors, said Sarah Straveler, RN, a clinical coordinator for the Pediatric Blood and Bone Marrow Transplant Program at Helen DeVos Children’s Hospital.

Anyone between age 18 and 44 may sign up for the registry by donating a sample of cells, generally done through a simple swab on the inside of the cheek. Through a process called human leukocyte antigen typing, the protein markers in the sample are recorded and compared to those needed by patients with leukemia or other blood diseases.

If preliminary matching occurs, more sophisticated testing and analysis takes place, assuming the donor agrees to participate. Donors also undergo a physical exam and chest X-ray.

As long as a donor isn’t disqualified because of poor health or another reason, such as testing positive for hepatitis or HIV, possible dates for the donation are discussed and a schedule is created.

“There are lots of forms to fill out and boxes to check,” Straveler said. “We need all this information back before we can start chemotherapy.”

For 10 of the 11 days leading up to her transplant, Lilly underwent a low-intensity chemotherapy regimen and a radiation treatment designed to wipe out her immune system so it would not reject the new bone marrow. Ideally, Lilly’s body will acclimate to the change and doctors will begin to see evidence of new cells within the next two or three weeks.

While Lilly has felt pretty good since she her admission to the hospital two weeks ago, now is the time when she is likely to feel the most tired and ill because her blood counts are really low and she may experience side effects from the chemotherapy, said Ulrich Duffner, MD, director of clinical services for the Pediatric Blood and Bone Marrow Transplant Program.

“And the risk of infection will last for many months,” he said.

Processing marrow

Before Lilly received the fluids she calls her “gift of life,” they were harvested from the pelvis of a female donor in Europe.

That outpatient procedure, done under general anesthesia, generally takes 60-90 minutes.

“Most donors stay in the hospital for four to five hours,” Straveler said. “We tell people they will be sore, like if they fell on icy pavement, and they might feel tired for a couple of weeks.”

From there, a certified courier picked up the bone marrow and carried it in a small cooler to Michigan Blood corporate headquarters in Grand Rapids.

At Michigan Blood, the red blood cells and plasma were removed, leaving a concentrated bone marrow product with blood stem cells. Processing reduces the volume from 34 ounces to 7 ounces and changes the color from bright red to pinkish.

Lilly received her transplant within 48 hours of its harvest.

The rules governing all blood and bone marrow transports are strict.

“Couriers must have the product with them at all times,” Straveler said. “If they are flying, they can’t put it through an X-ray machine. It comes with a certified letter. They can’t put it in the overhead bins and they are not supposed to sleep. They need to be available to protect it at all times … and when people ask, they are not supposed to talk about it.”

Helen DeVos Children’s Hospital also is a donor facility, so the procedure to harvest bone marrow and transport it elsewhere occurs here, too.

Next steps

Lilly and her family don’t know much about her donor and won’t be permitted to initiate direct contact for two years.

Each registry has its own rules about putting the donor and recipient in contact with one another, although the rule at U.S. hospitals and registries is generally 12 months of anonymity. In all cases, both parties must agree to disclose their identity before any information is exchanged.

In the meantime, Lilly and her parents penned several questions that Straveler plans to pass along to the registry in Europe in hopes that at least some of them will make their way to her donor.

In the letter, Lilly introduces herself, explaining that she likes to play basketball and collect stuffed animals. Mostly, the Vanden Bosches would like to know why the donor signed up and how she felt when she learned she was a match.

Before they are given to Lilly’s donor, the questions will be screened and those that might jeopardize confidentiality will be removed.

“Some patients have no desire to meet the donor,” Straveler said, although she knows of one instance when a local recipient traveled to New York to meet and thank a donor the day after the donor’s identity was disclosed.

A decade ago, the chances that a patient like Lilly would have a successful transplant were less than 50 percent, said Aly Abdel-Mageed, MD, section chief for the Pediatric Blood and Bone Marrow Transplant Program.

Today, about 80 percent of pediatric patients have a positive outcome, thanks in great part to more sophisticated matching of donors and recipients. In Lilly’s case, it’s more like 80 to 90 percent because of the high quality of the match.

The key to success is securing a close match between donor and recipient.

Patients like Lilly are more likely to find quality matches because donor registries are filled largely with Caucasians. Minorities often aren’t as lucky, which is something Lilly’s family would like to help change.

The Vanden Bosch family and Tom’s employer, S2 Yachts in Holland, are working with Michigan Blood to organize a bone marrow drive and spread awareness about how easy it is to be included in the registry. In conjunction with Be The Match, an initiative to boost the number of potential donors, Michigan Blood has set up an online link for people who want to sign up in support of Lilly.

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>