In 1970, most 10-year-old girls were adjusting Crissy doll’s hair length or trying on new bell bottoms.

Judy Bode was fighting cancer.

Fortunately, when we flash forward more than four decades, Bode is still among us, but unfortunately, still fighting the late effects of cancer treatments.

She’s gone to great lengths to educate the world about her experience, including creating a documentary called “Resilient,” that details the lingering side effects of cancer treatment.

She herself ended up with several other cancers after her childhood bout, and damage to her heart that she says directly relate back to her childhood radiation.

So it begins

It all began on a seemingly ordinary day: Dec. 1, 1970.

“I woke up with a lump in my neck that morning,” the now 55-year-old Bode said. “I was perfectly healthy, then I was diagnosed with Hodgkin’s lymphoma, stage 2. Of course, in 1970, no one was being cured of that.”

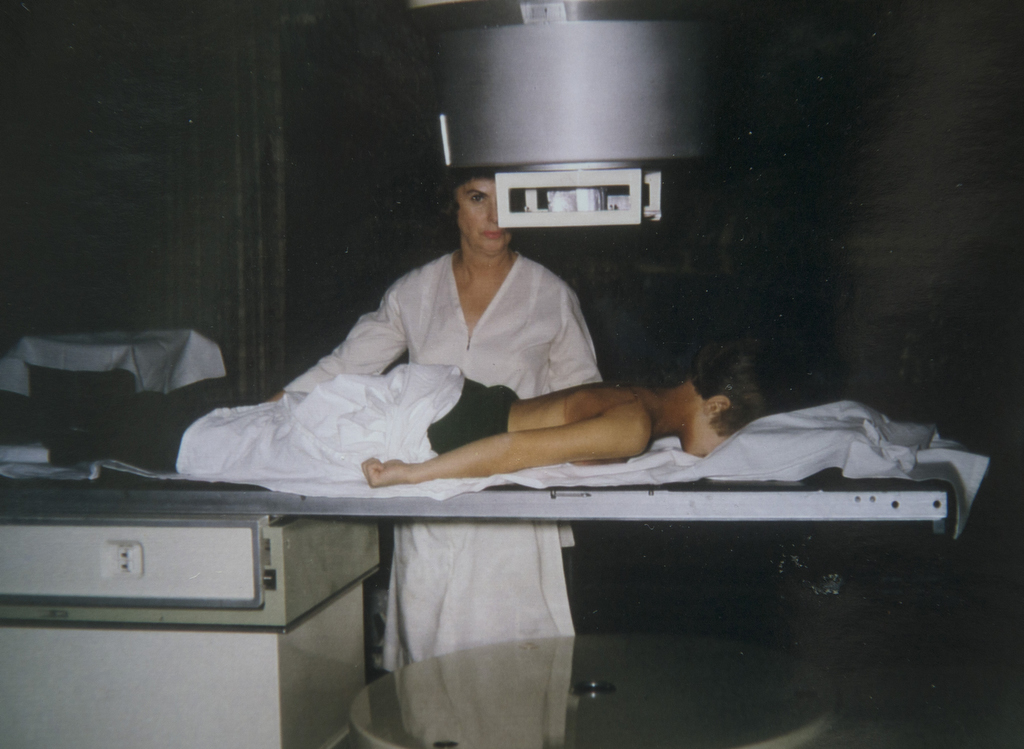

Bode said at the time, she was the youngest patient treated for Hodgkin’s lymphoma at Butterworth Hospital—radiation therapy from her chin to her diaphragm.

“The good news my parents were given was that I might live three years,” Bode recalled. “That was the optimism they initially gave my parents, that they might have three years left with me. That was 45 years ago.”

Bode recovered and went on to play tennis at Grand Rapids Christian High School. Just as cancer couldn’t beat her as a kid, no one could beat her on the court. She finished her high school career undefeated.

Inspired by her time there as a child, she became a nurse at Butterworth Hospital, then married her husband, Dan, in 1982 and had two children.

Radioactive relationships

“The pregnancies took a toll on my heart,” Bode said. “When I was 29, I was diagnosed with thyroid cancer. The thyroid was in the middle of the field of radiation I had received when I was a kid. The thyroid is sensitive to radiation, especially in a developing child.”

There is a cost for curing cancer. Those side effects we don’t necessarily see right away.

Surgeons removed three-quarters of her thyroid in 1990. But because the entire organ had been exposed to radiation, the danger lurked that the remaining one quarter could become cancerous.

She underwent two rounds of radioactive iodine.

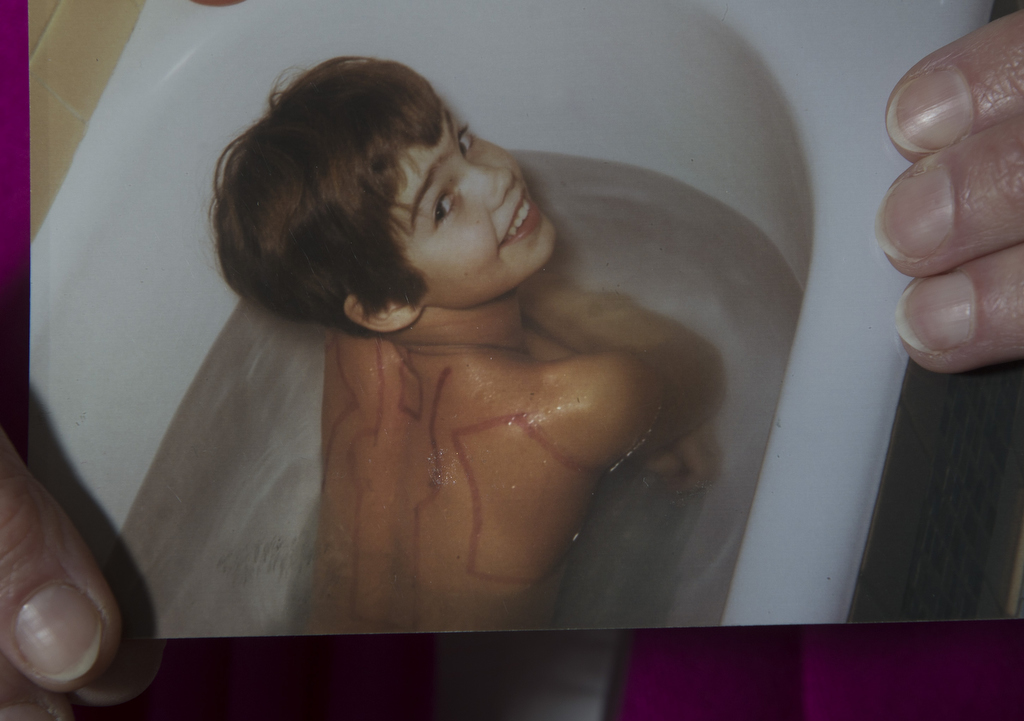

“It was terrible,” she recalled. “Our kids were toddlers at the time. For five weeks after the first dose I had to stay at least five feet away from my kids (because of the radioactivity). I couldn’t ride in the car with them. I couldn’t pass them in the hallway. I couldn’t brush their hair. That was probably the worst five weeks of my life.”

She went into remission and continued to raise her children, Brian and Amanda, in non-radioactive fashion.

Cancer, round 3

But eight years later, her oncologist informed her that young girls treated with radiation have an extremely high chance of developing breast cancer. He recommended mastectomies.

She was 38.

“It took me many months to come to that decision and be comfortable with it,” Bode said. “Finally, I decided it was indeed the right thing to do.”

John O’Donnell, MD, a hematologist affiliated with Spectrum Health Cancer Center, said radiation can damage developing breasts, making Bode’s cancer risk high.

“We were removing the breasts to prevent Judy from ever getting cancer, but when we looked at every part of her breast tissue, she had cancer that we couldn’t detect by any other means,” Dr. O’Donnell said.

Because of early detection, Bode did not need further treatment.

A year later, she picked up an old love—tennis.

“That was almost a miracle in and of itself,” she said. “But I started to get chest pain when I was running and playing. Here I was, 39 years old, playing with retired ladies and they’re running circles around me. I was short of breath, tired and had chest pain. That’s when they started a whole year of testing my heart and lungs.”

Bode went to an out-of-state hospital on a Monday and was in surgery on Friday for two coronary artery bypasses.

“I came home a week later and basically went into heart failure,” she said. “I couldn’t breathe. I was retaining fluid.”

I waited three and a half years—three years, six months and two days—on that transplant list, every day wondering if that was going to be the day that I was going to get called or the day I was going to die.

She learned that the bypass grafts had failed and ended up with stents. But there was another problem—inflammation of the pericardium, the sac around her heart—another lasting effect from the 1970 radiation.

“When you open up a radiated chest with all the scarring, there’s this cascade of events that can lead to an incredible inflammatory response,” Bode said. “I was in heart failure and never came out of it.”

Next stop, heart transplant

“I crept along for those few years but we knew a heart transplant was inevitable,” Bode said. “Because my case was so high-risk, most transplant centers would not even accept me.”

She was listed on the national transplant list in March 2010.

“We were waiting for the only thing that could help—a heart transplant,” Dr. O’Donnell said.

Bode remained realistic about her potential outcome.

“I was dying,” she said. “I knew it. I knew the only way I was going to get a heart was through the gift of someone else who already had died.”

But there was another issue—fit. Because of the radiation as a child, Bode’s chest is small. Her shoulders, neck and ribs never really grew. She needed the heart of a child.

Her life was spared as a child. Now, she needed a child to save her.

“You know someone would have to make a decision in a time of utter grief,” she said. “That thought was never far from my mind. I waited three and a half years—three years, six months and two days—on that transplant list, every day wondering if that was going to be the day that I was going to get called or the day I was going to die.”

On Sept. 5, 2013, the call came. “We have a heart for you,” the transplant coordinator told her.

Her documentary includes footage of her going into surgery, and the heart being delivered in a cooler.

Bode later received a letter from the donor’s family. The girl was 13, and died after a brief illness.

Sharing the late effects message

“I recovered for a year and here I am,” Bode said. “I’m feeling great; was able to get back to playing tennis.”

Bode formed a non-profit with a fellow childhood cancer survivor who also had a heart transplant in adulthood and filmed “Resilient,” a documentary focusing on the effects of cancer treatment.

“So many physicians do not understand the late effects of cancer cures,” Bode said. “There are 14 million cancer survivors in the United States and hundreds of thousands of adult survivors of childhood cancer and each one is at risk for late effects.”

Beth Kurt, MD, a pediatric hematologist and oncologist at Spectrum Health Helen DeVos Children’s Hospital, appeared in Bode’s documentary.

“There is a cost for curing cancer,” Dr. Kurt said, explaining that exposure to chemo and radiation can cause lasting side effects. Some medications even affect the heart and its squeezing function. “Those side effects we don’t necessarily see right away. The good news is that over the decades we have learned better ways to treat and cure children with cancer, while minimizing or even avoiding some of the more toxic therapies for many patients.”

There’s also plenty of support when those child cancer survivors become adults.

“We encourage survivors to make good informed choices about their health and maintain regular medical follow-up so that they are armed with the right tools to live long, healthy lives,” Dr. Kurt said.

The Spectrum Health Cancer Center provides programs for cancer survivors that focus on the effects of cancer treatment on the heart, care for chemotherapy side effects such as “chemo brain” and neuropathies and acupuncture, according to its chief, Judy Smith, MD.

“Our multidisciplinary team of cancer specialists is engaged in clinical trials and research looking to advance the care of all patients, including the identification of treatments that may potentially be as effective but have less toxicity and fewer long-term effects,” Dr. Smith said.

Bode has taken it upon herself to educate, scheduling documentary screenings for medical school students and physicians.

“’Resilient’ is the story of cancer, the story of pain, the story of late effects and the story of hope through gifted hearts,” Bode said. “In sharing my story, we hope to educate and equip cancer patients and the medical community about the challenging subject of late effects.”

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

Where can “Resilient” be found?

Hi Gloria – You should be able to get a copy through this link: http://www.myheartyourhands.org/ Thanks for being a Health Beat reader and for your kind comments! 🙂

If only the forsight had been there in the 70’s-80’s but I am glad that you and my mother survived. She will be 52 this year and has been dealing with late term effects from recieving radiation treatment at 16 for hodgkin’s lymphoma. She just underwent valve replacement surgery in Feb. 2015 and now has cancer for the 3rd time (sarcoma). Thank you for creating this documentary to educate, I hope to be able to check it out soon.

Your blog is very informative. I really appreciate your work. When my son was 8 years old, he was eating whatever he wanted because he simply didn’t understand that junk food wasn’t good for him. Fast food became a regular part of his diet – several times a week at least! Long story short, before too long, my son got really sick. He had very weak immune system problems which meant that the usual colds and flu were becoming serious illnesses for him. When we discussed it with the experts, he was detected with cancer. It’s been 4 years now and he is still fighting with it. Now he has become more conscious about what he ate and how healthy he has to be. All the treatments were done on time by the specialists with the latest technology. I request everyone to take good care of their children and monitor their diets and most importantly have regular check-ups.