In 2016, at 20 weeks pregnant, Aleigha Pruitt felt something unusual grip her belly.

She had her husband, Justin Pruitt, put his hand on her belly to see if he felt anything.

“It was visible, and it felt like the baby was having some kind of seizure,” she said. “It was my fifth pregnancy, to be my second live birth, so I knew something wasn’t right.”

She later had an ultrasound, which showed a large mass. Pruitt was taken directly to delivery.

Her little boy entered the world via C-section on Dec. 14, 2016.

“I was told not to listen for a cry when the baby was born, but there was a cry right away,” Pruitt said. “And the mass turned out to be a brain bleed.”

They named him Junior, short for Justin Jr.

Pruitt quickly learned her baby might not make it through the night.

An ambulance rushed Junior to Spectrum Health Helen DeVos Children’s Hospital, where he went directly to the neonatal intensive care unit.

“I remember it was blizzarding that December day as my mom drove me to Helen DeVos Children’s Hospital from Muskegon, where we lived back then,” Pruitt said. “We made it in 25 minutes.”

Doctors immediately worked to increase his platelet count.

Junior made it through the night.

The morning, however, brought slim hope.

Doctors diagnosed Junior with post-hemorrhagic hydrocephalus, more commonly known as water on the brain. It’s caused by disturbances in cerebrospinal fluid flow following a brain hemorrhage.

“We were told our baby may be cognitively impaired, that he may be blind and deaf,” Pruitt said. “No words for how that felt. I didn’t want a sugar-coated diagnosis, but I was looking for hope.”

Junior survived the day. Then the next. And the next.

Pruitt found the hope she needed.

“A doctor told us that no one can really know Junior’s future,” Pruitt said. “Junior may have disabilities or he may do well. All I could do was to focus on doing our best for him.”

New year, new challenges

By Christmas, the Pruitts brought their baby home.

“He was jaundiced and couldn’t process the bleed, so he was readmitted a few days later,” Pruitt said. “In January 2017, Junior had his first brain surgery for placement of a reservoir.”

Doctors placed a ventricular access device, a kind of port, into Junior’s brain to drain excess fluid.

The family dog, a Siberian husky named Storm, always seemed to know when something was wrong with Junior. Pruitt learned to pay attention.

“Storm was fussing over Junior,” Pruitt said. “And I noticed a sudden increase in Junior’s head circumference. We brought Junior in for imaging and, the next morning—that was in March 2017—Junior had his first shunt placed.”

A shunt is a hollow tube that’s surgically placed in the brain to help drain cerebrospinal fluid. The fluid normally bathes the brain and delivers nutrients.

“Junior was doing well,” Pruitt said. “By seven months, he was crawling. By about a year, he was walking with a walker. And at 13 months, he was walking on his own, running and jumping.”

They were also able to remove braces he’d been wearing on his legs since about eight months old.

“He was at age level, cognitively,” Pruitt said.

They were all good signs.

Over four years, Junior would undergo 28 brain surgeries, mostly to replace shunts.

Spectrum Health pediatric neurosurgeon Casey Madura, MD, has treated Junior since summer 2019.

“Every shunt problem is different,” Dr. Madura said. “Junior has had to have shunts replaced frequently, while others can go years without a replacement.”

Bacterial meningitis

Still other challenges arose.

In March 2019, all five members of the Pruitt family came down with the flu, including Junior.

“I had to wonder with Junior—was it the flu or was his shunt failing?” Pruitt said. “His temperature was spiking, he was throwing up and losing his balance. So my husband took him to the pediatrician, who then told us to bring him to the hospital.”

Junior’s flu had turned into bacterial meningitis, which can keep the brain from absorbing cerebrospinal fluid. And he had suffered another stroke, much like the one doctors believe he had suffered in utero.

Once again, the Pruitts faced the possibility of losing their son.

“He was in the hospital from March to August 2019,” Pruitt said. “I was told he may not survive.”

After yet another surgery, Junior opened his eyes on Day 52.

He crawled out of bed and walked into the bright hospital hallway.

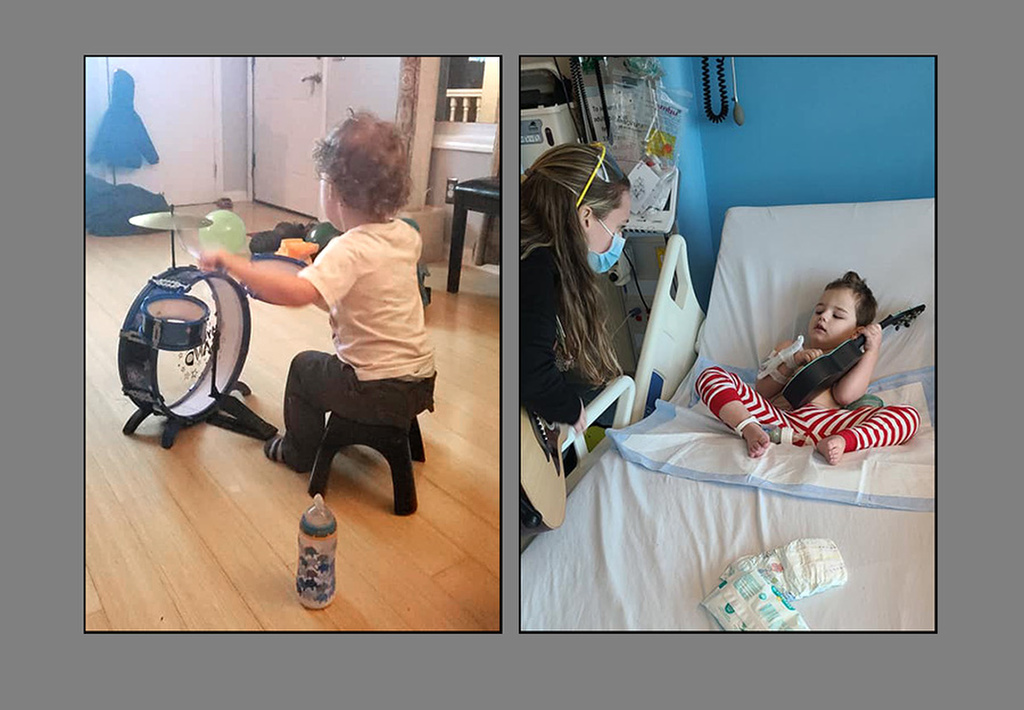

Music power

Junior left the hospital in a wheelchair, and he had lost his verbal skills, but Pruitt felt determined to help him recover lost abilities.

“I kept hearing this voice in my head,” she said. “I guess you could call it gut intuition. Sounds crazy, but that voice kept telling me: ‘Make him laugh.’”

She made funny faces and played the clown, anything to get her son to crack a smile.

“I also always have music on in the house,” Pruitt said. “And I noticed Junior responding to the music. He would sing along with Lady Gaga and he would cry with emotion as he sang.”

On his many visits to the hospital for treatment, Junior soon came into contact with Bridget Sova, a music therapist with the Edward and June Prein Family Music Therapy Program at Helen DeVos Children’s Hospital.

“Music is how Junior communicates,” Sova said. “Junior enjoys music beyond what most children do. He listens closely when I play for him and the music soothes him when he is upset.”

It also raises his energy levels when he’s in a good mood, Sova said.

More importantly, the music helped calm Junior so he could rest long enough to let the fluid drain from his head.

“He has an external tube attached to his head for drainage—and Junior must lie very still during that,” Sova said. “That’s hard for a kid. But I would strum my ukulele and he would listen and lie very still.”

Pruitt bought a ukulele for her son to strum at home.

“Music is his path,” she said. “When Bridget comes in, it just changes him.”

Moving forward

“We currently have only three such cases in treatment,” Dr. Madura said. “Yet these kinds of bleeds can be more common than you might think. You may not realize it’s happened.”

It’s important for parents to remain vigilant, as Pruitt was, and to contact pediatricians if they suspect a problem.

“Communication is key,” Dr. Madura said. “If you are concerned, call us.”

Three years later, Junior is still working hard on making a full recovery.

“Junior has found some of his words but is expressing himself and playing with his voice more and more every day,” Pruitt said.

As for his physical abilities, he has steadily made small gains since going home. Junior can now control his head, has regained movement of his left side that was affected by the stroke, and loves getting into everything in his gait trainer.

“He also loves bike rides and sitting unassisted playing with toys, and he has age-appropriate comprehension skills,” she said. “His rehabilitation team thinks that, once he regains most of his physical abilities, that his verbal will really start to shine!”

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>