A recipe is only as good as its ingredients.

The kitchen is one of the best places to think about good medicine. Few know that better than the families of children who have compromised immune systems.

Lyndi Hollinger, 12, of Sparta, Michigan, knows it well. She received a kidney transplant at age 9—thanks to her uncle, Daryl Scheidel, who donated his. After years of kidney dialysis to keep her alive, she is watching her diet and taking good care of this one.

“Although I’ll probably need another one, maybe in 10 years or so,” she says.

“The disease is back again,” her mother, Tressa Hollinger, says with a nod.

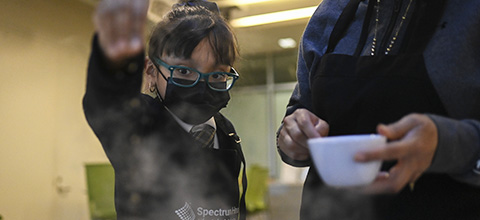

The two sit in a culinary class, offered by Spectrum Health Culinary Medicine, at the Children’s Healing Center, located in Grand Rapids. The culinary medicine program brings together health care professional and community members to understand how to use food as a tool in achieving optimal health.

Culinary class members have been tasting and testing, chopping and dicing for a few classes now. Currently, they’re filling cups with prepared ingredients for a pot of chili they will cook later at home, in their own kitchen.

A safe place

The Hollingers come often to the Children’s Healing Center. It’s a bit more fun than Lyndi’s many stays at Spectrum Health Helen DeVos Children’s Hospital.

The Children’s Healing Center is a 7,000-square foot space that provides a safe, clean place for children like Lyndi, who have compromised immune systems, and their families to gather, learn and play with staff.

Amanda Barbour established the center in 2015. Surviving Stage 4 Hodgkin’s lymphoma taught Barbour compassion for the many who must fear every germ, every virus, that might send them spinning into a hospital bed. She created the Children’s Healing Center to give kids an oasis from disease, if even just for an occasional hour of play.

“We have an exploratory play area, a fitness area, a tech zone, a quiet room, and an art and learning room,” says Liz Greer, volunteer coordinator.

Greer greets every visitor at the door, where she guides them to a staff member who takes the visitor’s temperature with a quick swipe across the forehead, then nudges the visitor along to take a seat while wiping down shoes. Next, wash hands. Only then enter the rooms deeper inside.

“We pride ourselves on no germs, but this is a place where we want all kids to feel, well, normal. Like every other kid,” Greer says. “I have a special needs daughter, 11 years old, and she comes here. I know what it means to be here.”

Cooking up good health

This night’s culinary program, she explains, is only one program of a great many. With 800 active members, serving more than 1,300 people since 2015, the center’s staff stays busy and so do the kids who come to them.

The idea for the trio of culinary classes over three weeks came from Elizabeth Suvedi, culinary medicine chef at Spectrum Health.

The room is filled on this evening as three physicians teach the virtues of cooking with whole foods.

Allison Engel, MD, and Melissa Keeley, MD, are second-year residents in pediatrics at Helen DeVos Children’s Hospital.

Kristi Artz, MD, medical director of lifestyle medicine and physician lead for the culinary medicine program, is the instructor for this night’s class. Her hands are full of bell peppers and onions as she demonstrates how to cut each, first slicing off a flat side so the vegetable doesn’t roll off the table.

“Who is brave enough to taste a raw onion?” Dr. Artz calls out, holding up a red onion. Several volunteer.

Placed around tables with their parents, the kids dutifully cut the vegetables in front of them on cutting boards. They have learned about making healthy snacks, breakfasts and now dinners.

Dr. Artz talks about the health benefits of eating beans and other legumes.

“High protein, fiber,” she lists. “You don’t have to always have meat on your plate. And you can save money, too. A pound of beans might cost you around $1.44, but a pound of ground beef could run you around $4.34.”

Flavored with faith

For Lyndi Hollinger, it is important to watch her intake of sodium, potassium and phosphorus. She has to think about a healthy renal diet, appropriate for those with kidney disease.

By age 2, doctors had identified a rare disease that caused kidney failure in Lyndi. They diagnosed her with focal segmental glomerulosclerosis, a type of disease that causes scarring of the kidney. It can have many different causes—an infection, a side effect of a drug, or from another disease that affects the body.

That isn’t all.

Lyndi also has nephrotic syndrome, a kidney disorder that causes the kidney to eliminate too much protein. It is caused by kidney damage. Symptoms include low blood albumin levels, high blood lipids, swelling, weight gain and fatigue.

The 12-year-old presses her chin into the palm of her hand and considers her circumstances. Her mother watches her.

“Sometime around July 2018, we decided to focus on the quality of life,” Tressa Hollinger says. “Not all of Lyndi’s treatments have been successful. She gets sick, and then she’s back in the hospital again for two or three days, or maybe weeks. Her face and lips get puffy and swollen when she catches a cold. Every simple thing can turn into a hospital stay.”

“I don’t know if there will be another kidney when I need one again,” Lyndi says. “I guess you just have to have faith.”

Her mother studies her as she talks. After a moment, she adds: “It’s OK to break sometimes. As long as you have a support system. And…” she looks around the room, at kids chopping vegetables and parents watching. “… it’s good to have a place like this, where your kid can come to have some fun and still be safe from getting sick again.”

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

Great article- testament to the incredible and comprehensive level of care delivered through HDVCH, plus the community and individual impact associated with Lifestyle/Culinary Medicine.

Just tell us what are the best beans to use!

Hi Marjorie! Thanks for your question. Holly Dykstra, a registered dietitian, said that black beans, kidney beans, chickpeas, lentils are all great. “Whatever your taste, beans are loaded with goodness,” she said. Enjoy!