Gray Rushin’s Instagram narrative begins like this:

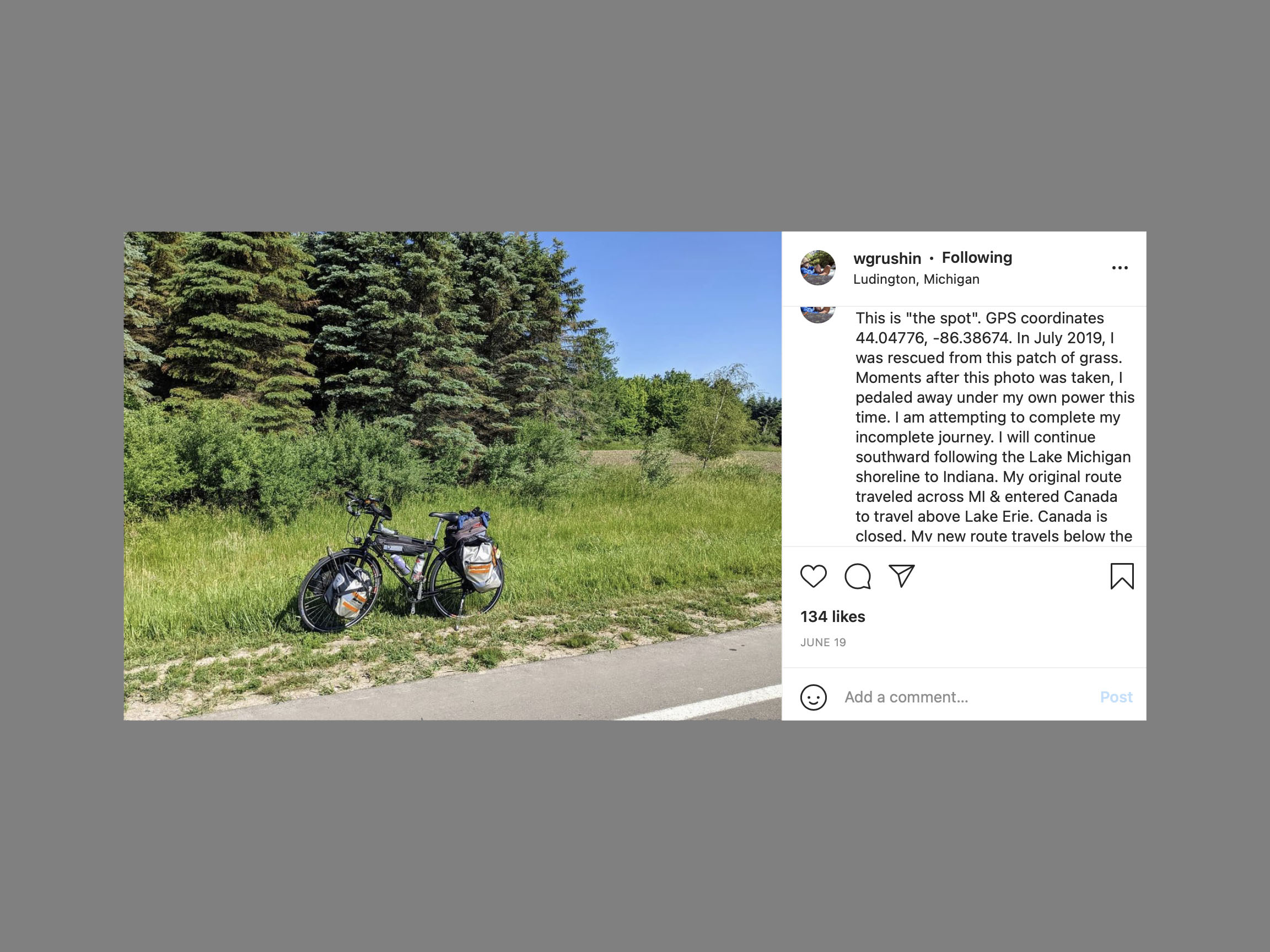

“I have returned to Michigan. This is ‘the spot.’ GPS coordinates 44.04776, -86.38674. In July 2019, I was rescued from this patch of grass.”

The Instagram posts recount his quest this past summer to complete a coast-to-coast bicycle trip that had been cut short two years earlier.

Cut short not by choice but by chance, when a tear developed in Rushin’s left carotid artery, creating a dissection and triggering a stroke.

The stroke hit without warning a month into his 2019 journey.

It pitched him onto the shoulder of a country road north of Ludington, Michigan.

Though he could think clearly, he couldn’t talk.

Couldn’t lift his right arm or use his hand.

Couldn’t continue pedaling.

With 3,000 miles behind him and another 1,700 miles to go before he’d reach the Maine coast, he faced a crushing detour—a 10-day hospitalization followed by months of grueling rehab.

Now, two years had passed.

On June 13, 2021, he returned with his bike to the precise patch of grass where he’d had to abandon his cross-country pursuit.

He stood ready to finish what he’d started.

People and places

Rushin, 57, a die-hard adventurer who lives in a house in the woods, is known to his friends as the “happy hermit.”

At the Cary, North Carolina, high school where he teaches chemistry, he also leads an outdoor adventure club.

In June, he drove to West Michigan and met up with his daughter, Sydney, who came in from Chicago.

Together they traveled the streets of Grand Rapids and Ludington, where he recalled the people he met in the early days of his stroke journey:

- The off-duty Michigan state trooper who saw him at the roadside and called 911

- The quick-witted ER staff at Spectrum Health Ludington Hospital who used his phone’s cycling app to pinpoint the time of his stroke and administered clot-busting medication

- The Aero Med helicopter pilot—who’s since become a friend—who airlifted him to the regional stroke center at Spectrum Health Butterworth Hospital

- The neurology team who removed the blood clot from his brain, stented the artery to hold it open and got him up and moving

- The therapists at Mary Free Bed Rehabilitation Hospital who initiated intense workouts and helped him get home, ahead of schedule

With those memories refreshed and Sydney at hand to see him off, Rushin couldn’t wait to get started.

“I was expecting it to be more emotional. I got to the spot, and I just felt charged up. Just—adrenaline, excitement. I just wanted to leave. I didn’t want to linger there,” he said.

“I took that picture, and I was just excited to move down the road and have my freedom again.”

Freedom to restart this personal quest.

Freedom to test his strength and agility after countless hours of self-directed rehab.

Freedom to dream of future great adventures.

“Losing control of your body is frightening,” he wrote for his Instagram community. “Regaining it is incredibly daunting, tedious, painful work. … I still have many questions; the open road holds some of the answers that I seek.”

Risks and rewards

Eight states—Michigan, Indiana, Ohio, Pennsylvania, New York, Vermont, New Hampshire and Maine—lay between Rushin and his goal.

He had a route and a plan.

He understood the risks and rewards.

“My legs are in their best pre-trip condition ever. But the mental game is tough,” he wrote on Instagram. “I’m supposed to be doubtful, nervous, scared … but my antidote is planning for, mitigating and accepting risk.”

Because his right hand and arm remained “compromised tools,” two risks stood out: Trouble using his bike’s grip shifter and the potential for hand numbness, an issue that had plagued him during the Washington-to-Michigan leg of his journey.

But neither problem ended up getting in his way—not even while crossing the Adirondacks, the Green Mountains and the White Mountains.

“Numbness never became a problem,” Rushin said.

“Eventually the shifting became a problem, and I solved that. I learned how to use my left hand to reach across and do the shifting. I wouldn’t recommend it—you can lose your balance quick—but I learned how to do it safely.”

He had packed his Kindle in case he’d need to take a day off along the way, but he never used it.

“I pedaled every day and was happy for it,” he later wrote.

Set up for success

Rushin’s remarkable rebound came as no great surprise to Muhib Khan, MD, the Spectrum Health stroke program director.

His lifestyle set him up for success.

“One of the things that we have learned in the stroke world is your chances of recovery are much better if you were physically very active before the stroke happened,” Dr. Khan said.

“And he is beyond physically active.”

During the handful of days the cyclist spent at Butterworth Hospital, Dr. Khan witnessed his unstoppable drive and sheer physical strength—qualities forged by experience.

“(Rehab) was new to him, but his body and his mind is set to work and push himself, because that’s what he does when he bikes, right? … So that kind of training helped him,” Dr. Khan said.

“Even at that time, he told us that he’s going to come back here on a bike at some point.”

Rushin finished his ride in Rockport, Maine, on July 1.

“I completed my ocean-to-ocean crossing in the harbor of Rockport, ME,” he posted on Instagram. “The waves of emotion within me were more powerful than the waves offered in this protected harbor.”

Though his full route took him further up the coast to Bar Harbor, he prizes the moment his tires touched the Atlantic.

“I felt that I had achieved the journey at that point because I’d made it ocean to ocean,” he said.

The poignant emotions that eluded him at the start of his 19-day ride now washed over him.

“It was overwhelming. So what I thought I would feel at the beginning, I definitely felt at the end.”

His statistics: 4,705 miles pedaled, through hundreds of towns in 14 states and a Canadian province.

In Rockport’s peaceful harbor, he reflected on the times when “giving up on my adventuring ways felt like the wisest choice.”

He felt gratitude for the “abundance of support” that helped him on his way.

Summing up his motivations, he wrote: “I wander and explore … and tolerate hardship … because I know the end game, the final ledger, will be much heavier in personal reward than personal suffering.”

In finishing what he’d started two years before, Rushin gained the assurance that he could keep doing this thing that he loves—this adventuring, this gathering up of profound experiences.

“I just have this internal drive, where I guess I’m kind of competitive with myself … (and) I didn’t want that to be taken away from me,” he said.

“Now I know that, looking forward, I can plan another cross-country trip or similar long-distance trips and have the confidence that I can do it.”

Rushin plans to continue his physical therapy regimen in his own way, rebuilding his hand strength as he pursues specific functional goals.

“It’s still steady progress. It could take five years, maybe, but I wouldn’t be shocked if I got back to full function, or close,” he said.

He hopes his cycling achievement can encourage others sidelined by stroke to fight for their recovery, despite the struggle.

“I want people to have hope and to feel like anything’s possible,” he said.

“It’s a happier finish this time.”

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>