It was a hot and humid evening on June 18 when Jeremiah Vroegindewey arrived for his first co-ed adult league soccer game at East Grand Rapids High School.

“I remember a little bit of playing, and I remember I had one shot on goal, but it went over the bar,” the 22-year-old said.

That’s all he remembers.

The person who recalls every excruciating detail is the woman who helped save his life that night on the soccer field—his teammate Megan Zabawa, who also happens to be a physician assistant with the orthopedic trauma group at Spectrum Health Butterworth Hospital.

She has re-played every moment over and over in her head: rushing to him after he collapsed on the field, seeing him go into cardiac arrest, performing CPR, and helping paramedics shock him back to life with an automatic external defibrillator.

“It was a horrific night. When I called my mom and told her about what happened, she told me I was a hero and I saved his life. But honestly, that’s not the feeling you get,” Zabawa said. “We all thought he was dead. It’s an absolute miracle and blessing that he is OK. It’s easier to talk about now that I know he’s doing OK.”

In fact, only 8 percent of people who suffer sudden out-of-hospital cardiac arrest survive, according to Al Albano, MD, a cardiologist with Spectrum Health Medical Group.

“This survival rate has improved only 3 percent over the past 10 years, in part due to the short window of time that treatment needs to be delivered in order to be effective,” Dr. Albano said.

Zabawa is a big reason Vroegindewey defied the statistics.

“This highlights the importance of CPR training and knowing what to do when somebody abruptly loses consciousness,” Dr. Albano said. “Jeremiah was lucky he had someone around who knew what to do.”

‘A little medic with me’

Vroegindewey, who works as a surgical support technician at Spectrum Health Butterworth Hospital, knew Zabawa before that night, as she’s married to his friend, Lane. They also sometimes saw each other in passing while working at the hospital.

But he never could have anticipated how their lives would intersect.

“I really see God’s hand in bringing everything together,” Vroegindewey said.

What Jeremiah didn’t know that night is that he has arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. It’s a genetic condition that causes healthy heart muscle to gradually be replaced by fibrous tissue, according to David Fermin, MD, a cardiologist with Spectrum Health Medical Group.

That tissue, which is like scar tissue, causes heart arrhythmias or heart failure that put patients like Vroegindewey at risk for cardiac arrest.

What’s worse is that soccer, the sport Vroegindewey loves, exacerbates the condition by putting his heart under more strain.

“Heavier exertion may cause more long-term damage, which increases the risk of cardiac arrest,” Dr. Fermin said. “That is why we recommend that anyone with (this condition), not just young athletes, avoid repeated heavy exertion, such as competitive or contact sports, or occupations that require a high level of physical exertion.”

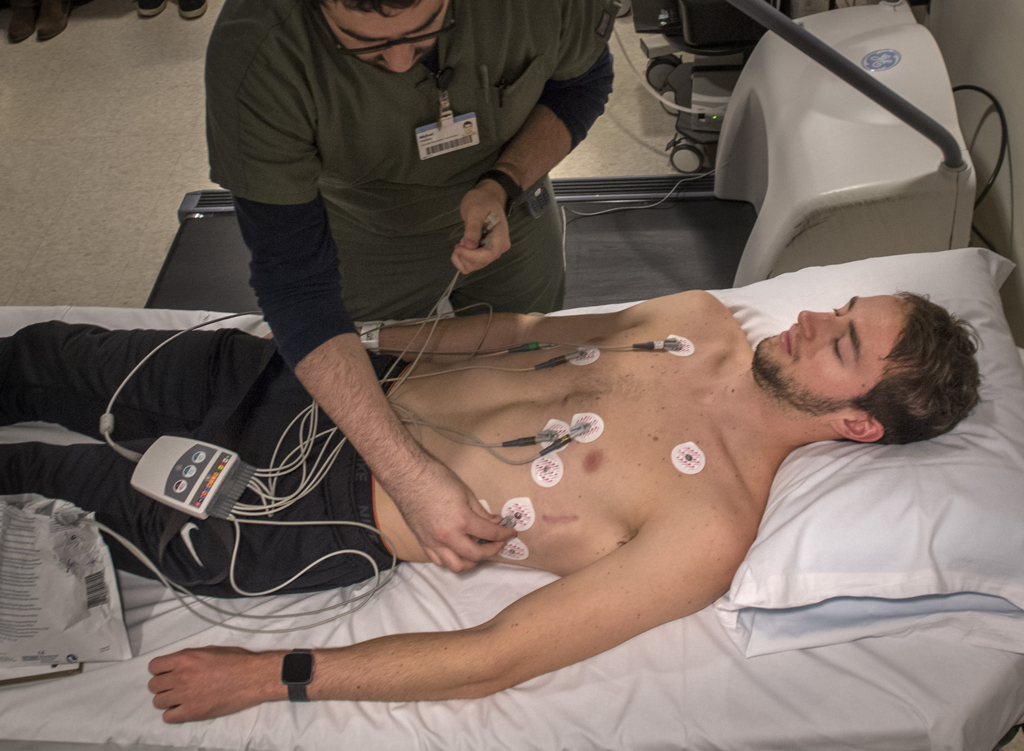

Two days after Vroegindewey’s cardiac arrest, heart surgeons implanted a defibrillator in his armpit. It’s designed to sense when Jeremiah’s heart goes into arrythmia, and will then shock his heart to prevent cardiac arrest.

Knowing it’s there puts Vroegindewey at ease as he learns to live with this condition.

“It’s like a little medic with me at all times,” he said.

But Vroegindewey has still had to learn to go easy on his heart, keeping his heart rate below 120 beats per minute. In fact, one time since his cardiac arrest, a few weeks after leaving the hospital, the defibrillator did activate and shock him.

“I was at the YMCA kicking a ball around with my brother, and I had worked out before then,” he said. “I felt OK, but I guess I was running around too much.”

It’s hard for Vroegindewey to slow down.

“I have been trying to find other things to do,” he said. “I can’t play an actual soccer game anymore, but I can kick around a soccer ball.”

‘Everything just came together’

While the diagnosis overwhelmed Vroegindewey, it did not come as a complete surprise. He knew his aunt had this condition. It did help him to understand some things, like why he had been getting lightheaded while playing indoor soccer last winter.

“I didn’t know what it was. I thought I just wasn’t breathing right,” he said. “Now, I’m sure I was in tachycardia.”

Because it is a genetic condition, Vroegindewey’s family members have since been tested by Dr. Albano for the condition. He continues to see Drs. Albano and Fermin to manage both his defibrillator and medication. He’s “very thankful” for all the ways they and their teams have helped.

As for Zabawa, Vroegindewey sees her at work, and his family and hers went out to dinner since that night.

The emotions surrounding that night are still a bit raw for Zabawa. It was the first time she ever did CPR outside of a training class.

“You hope to never be put in that situation, but me having the knowledge that I do, I was able to perform CPR to help save his life,” Zabawa said. “If that’s the only positive thing that comes out of my career, I would say it’s a career well spent.”

Dr. Albano and Dr. Fermin stressed the importance of more people being trained in basic lifesaving, including CPR and proper use of an AED.

“Every second is critical,” Dr. Fermin said, noting that it’s also important for public places to have AEDs available.

“(This) may be one of the most impactful interventions in saving lives from cardiac arrest,” Dr. Fermin said. “This does not just apply to athletes—an AED is more likely to be needed for a spectator than an athlete on the field.”

Vroegindewey counts himself blessed to have had both quality CPR and an AED available to him.

“Everything just came together,” he said. “It’s amazing to see that.”

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

One proud Mom! Love you Megan Thornton Zabawa!