Robert Connors, MD, is an open, affable guy with a fistful of medical credentials that would surely impress even the most seasoned professionals at Spectrum Health Helen DeVos Children’s Hospital.

He’s not only a well-regarded pediatric surgeon; Dr. Connors runs the place, serving as hospital president since 2005. So when he asked everyone to call him “Bob,” more than a few staffers had their doubts.

“One nurse told me, ‘I just can’t do it,’” Dr. Connors laughs. “I said, ‘Sure you can. Just say, Good morning, Bob.’”

He’s not just trying to be friendly.

Dr. Connors believes that the titles he and his fellow doctors carry with them create a hierarchy that can intimidate others on their medical teams.

And that intimidation can lead to poor communication among colleagues when they need it most.

So last June, he asked all staff to refer to hospital physicians by their first names or preferred nicknames, starting with Dr. Connors—uh, Bob—himself. In February, he put everyone else at the hospital on a first-name basis.

He says that one of the keys to effective communication is being able to raise concerns without a barrier between staff members. One of the code phrases team members use is, ‘I have a concern.’

“When you say, ‘I have a concern,'” Dr. Connors explains, “what you mean is ‘Let’s hold on here, let’s stop. I have a concern about my patient’s safety.'”

“People have to feel free, no matter who’s in the room, to do that,” he adds. “But people will tell you they don’t feel comfortable raising that to someone above them on the org chart.”

Medical culture

Hospitals work hard to eliminate what are called hospital-acquired conditions, such as infections, Dr. Connors says.

In 2007, he launched a new safety program at the hospital, and the results were impressive: safety events declined 68 percent between 2008 and 2010. Hand hygiene improved dramatically, and spinal surgery infections were eliminated.

So it was with much dismay that a safety culture survey turned up some alarming news: Only half the staff said they felt free to question the decisions or actions of those with greater authority. And more than a third said they were afraid to ask questions when something didn’t seem right.

In a June 2014 memo to staff, Connors said he was surprised and discouraged by the findings and resolved to address them. And the “Call Me Bob” initiative was born.

“It is not about job confusion,” he wrote in the memo. “We will continue to use ‘doctor’ to describe a role on our teams. We just won’t use ‘Doctor’ as a title. It is also not about being less respectful of our physicians and the tremendous contributions they make to our patients.”

This is about us dropping our titles within our own teams, he reinforced.

“With your patients, you can absolutely say, ‘I’m Dr. Connors,'” he adds.

Titles are a privilege, and hard earned, especially for physicians, Dr. Connors acknowledges.

“Most of the doctors were for it,” he says. “I suspect some thought it was stupid. And others may have questioned how something that simple could have any impact.

“I wanted this to evolve on its own, but I also wanted there to be an expectation that we were doing this thing. You’re really getting at people’s culture, and it takes a while.”

Discomfort and disrespect

The initiative has not been without its ups and downs, says Christine Bernier, DO, division chief of pediatric anesthesiology. At first, she says, “some physicians felt disrespected, and some of the nurses didn’t feel comfortable calling the doctors by their first names.”

Some staffers even rebelled and found ways to communicate their displeasure.

“That first month, I had people actually calling me Bob,” Dr. Bernier says. “I felt disrespected by that. Others would tap me on the shoulder instead of using my first name.”

And as a female physician, Dr. Bernier says she faced another barrier: the tendency of patients and their families to think of women as nurses.

She recalls working with a certified nurse anesthesiologist who is an older, distinguished-looking man. When they used their first names, some parents took him for the doctor and her for the nurse.

She’s found a way around that. “Now I come in and say, ‘I’m Christine Bernier, and I’ll be the anesthesiologist doctor for your child.’”

Samantha Gruber, a surgical technologist who has worked at the hospital for 10 years, says the initiative has practical benefits. During a surgery, the team is responsible for counting the number of sponges, needles, instruments and other equipment they’re using.

“We count before the surgery to establish a baseline, and then we hold another count as they begin to close up the patient, to make sure we haven’t left anything inside,” she says.

“At first we weren’t used to using first names, but it’s good for the team,” she adds. “It’s a lot easier to say, ‘Hey Dan, hang on a second. We’ve got to find this sponge before you move on. Usually it’s on the floor or behind a drape, but we have to account for it.”

“Dan” is Dan Robertson, MD, a pediatric surgeon at the hospital. Gruber says Robertson is doing his part, teasing the resident physicians about hanging onto their titles.

“When the interns return a page, they tend to say, ‘this is Dr. So and So,” Gruber says. “Dan tells them, ‘They know you’re a doctor. That’s why they paged you.’”

Overcoming resistance

Is everyone on board? Dr. Bernier is circumspect. “I think people have settled in to what they’re comfortable with.”

Dr. Connors believes the initiative has won pretty broad acceptance, with a few exceptions.

“I’m holding sessions with the famous and loud resisters,” he jokes.

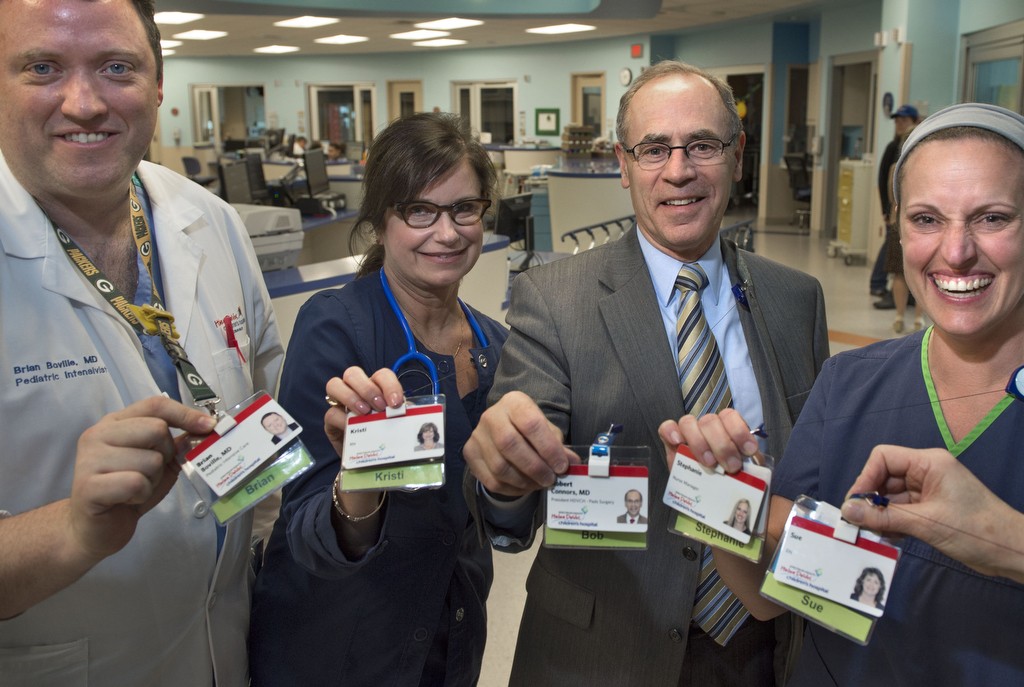

He even designed a new name badge with a clear backing, where each employee can choose the familiar name they’d like to use—and no one will miss.

“It’s very visible,” he says. “You don’t know everyone’s name, and now it’s easy to see.”

And just so no one would forget, Dr. Connors issued a second memo in February, called “Call me Bob … again,” urging all staff to use familiar names with their teammates.

“Just imagine: No more harm from hospital-acquired conditions; no more serious safety events,” he wrote. “And imagine yourself as part of America’s highest-performing patient safety team. We can do this together; I know I can count on you.

“As your teammate, I look forward to using your familiar name, and invite you all again to please call me Bob.”

The hospital will conduct another safety survey this fall to see if the initiative is making an impact. Dr. Connors expects the numbers to improve, but he stresses that survey metrics are not the only way to gauge the success of “Call Me Bob.”

“There are great advantages to doing this that are not as easy to measure,” he says. “It’s hard to measure things that used to happen and now don’t.

“We’re trying to address some traditional elements of medical culture that are not helpful to us. And the conversations we’re having are really valuable.”

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

Bob good to see you. Nice Safety idea.

Stay in touch.

Ron