Young Kody Brant adores animals and cars.

He loves to sing, dance, climb and play outside with his siblings, Kylee, 9, and Kaden, 6.

“He is my wild one,” his mom, Jolynn Brant, said.

“He is not afraid of anything. … He falls and he gets right back up.”

The gusto Kody demonstrates today is a far cry from how things started for the blue-eyed toddler from Fremont, Michigan.

“If you saw him, you would never think he has gone through everything that he has gone through,” Jolynn said.

Biliary atresia

Kody, who turns 2 in January, has a rare liver disease that showed up early in life as unrelenting jaundice.

In his first few weeks at home, everything seemed fine, Jolynn said.

Though he had newborn jaundice—a common condition—tests of his bilirubin levels showed no cause for concern. Doctors expected the situation to resolve on its own, as it typically does.

During a video visit with the family’s doctor’s office in the early days of the COVID-19 lockdown, Kody still looked jaundiced, but not enough to raise alarm.

But as he approached the 3-month mark, Jolynn knew something was wrong.

“My mom’s Costa Rican and I was born in Costa Rica, so (at first) I just thought he was olive complexioned,” she said.

“But then his eyes started getting really yellow.”

Soon his urine developed a strong odor and his stools turned near-white.

Panicked, Jolynn rushed Kody to the emergency department at their local hospital, Spectrum Health Gerber Memorial, in April 2020.

A blood test detected elevated levels of direct bilirubin, a substance his liver should have been processing and eliminating through his stools.

Suspecting pediatric liver disease, the emergency medicine team referred the family to Spectrum Health Helen DeVos Children’s Hospital in Grand Rapids.

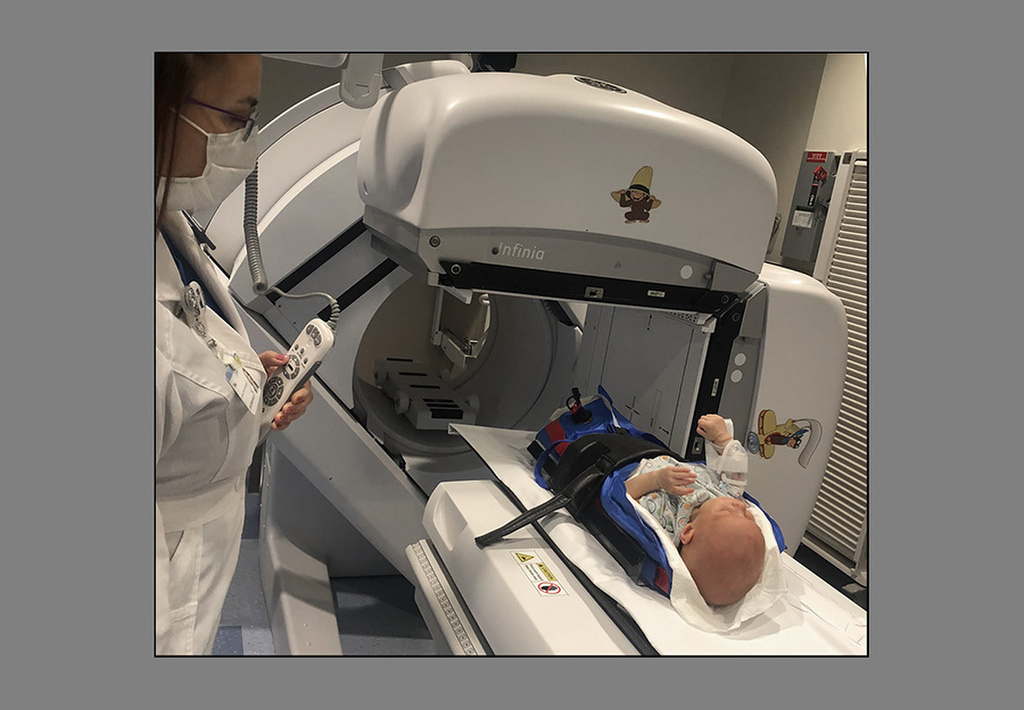

A series of tests—including lab studies, an ultrasound and a nuclear medicine test called a HIDA scan—pointed to a life-threatening disease called biliary atresia.

Meeting with a team from pediatric gastroenterology and pediatric surgery, the Brants got a crash course in biliary atresia and its standard treatment, an operation called the Kasai procedure.

In babies with biliary atresia, the ducts that carry bile from the liver to the gallbladder and small intestine become inflamed, causing scarring and blockage.

Bile therefore backs up in the liver and can’t reach the intestines. The longer the blockage persists, the more damage the liver suffers.

Medical experts aren’t certain what causes biliary atresia, though they know it’s not an inherited disease.

“The doctors assured me that there was nothing I did wrong or that could have prevented it,” Jolynn said.

Kasai procedure

In the Kasai procedure, a surgeon removes the infant’s damaged bile ducts and gallbladder, and connects the liver directly to the small intestine.

In bypassing the blocked pathway, the surgery promotes drainage to the liver, Marc Schlatter, MD, Kody’s pediatric surgeon, said.

“What it does is creates a path of least resistance for the bile, which is not really wanting to drain into a scarred-down duct.”

Because scarring worsens over time, the surgery works best when it’s performed in the first 60 days of a baby’s life.

In Kody’s case, the surgery took place on day 111, making its likelihood of success less certain.

The news was a lot for Jolynn and her husband, Kurt, to absorb.

“It was scary,” Jolynn said.

“I have a friend that’s a pediatric surgeon in Costa Rica, so I reached out to him, and he … thought that Kody was not going to make it. If he would have been in Costa Rica, he would have definitely not made it, he said, because they don’t have the medical resources … like the United States has.”

Kody’s surgery took place just before Mother’s Day weekend. He sailed through it.

Though Helen DeVos Children’s Hospital sees only one or two new cases of biliary atresia per year, Dr. Schlatter has operated on several of these patients in his 29 years of surgical practice.

To increase the surgical team’s exposure to the Kasai procedure, he asked a colleague, Elliot Pennington, MD, to join him in the OR.

Kody was discharged four days post-op. By then, his bilirubin levels had already begun to drop.

Still, Dr. Schlatter urged caution.

“What really matters is where they are maybe one to two months down the road. That gives you an idea of what way it’s going to go.”

Thankfully, things went in the right direction.

“When it works well, it works great,” Dr. Schlatter said, “and in Kody’s case it worked well.”

Pediatric hepatology

Kody, who had struggled to gain weight before the surgery—a common side effect of biliary atresia—went on a high-calorie formula and began playing catch-up.

Two months after his surgery, Sarah Henkel, MD, joined the pediatric gastroenterology team as its first specialist in pediatric hepatology.

She took on the management of Kody’s ongoing care, including educating the family about the potential complications of biliary atresia.

For example, a fever could signal cholangitis, an infection of the bile ducts caused by bacteria seeping up from the intestines. Cholangitis requires quick action: hospitalization and IV antibiotics.

Just days after Dr. Henkel discussed this risk with Jolynn in clinic, Kody developed a fever.

Knowing what to do, Jolynn got Kody to Helen DeVos Children’s Hospital for immediate care.

“It’s a difficult thing to manage,” Dr. Henkel said. “And his mom is really exceptional at being an advocate for her child and taking care of him.”

Today, a year and a half after surgery, Kody has easily made up for his bumpy start.

“He’s a growing, developmentally normal, really thriving toddler,” Dr. Henkel said.

“They’re out there living their best lives, going on trips, doing a lot.”

Yet, a few clouds remain on the horizon for the Brant family.

Even when the Kasai procedure is successful, the disease can still progress. There’s a significant chance Kody will need a liver transplant down the road.

“Unfortunately, most children with biliary atresia, about 90%, need a liver transplant by age 20,” Dr. Henkel said.

Whether Kody will be one of the lucky 10% is impossible to say. But for now, his prospects for a healthy childhood look good.

“With the way that Kody and Kody’s liver are looking right now, I would expect any progression of his liver disease to be very slow,” Dr. Henkel said.

“His childhood looks very bright at this point. But it’s a serious disease.”

Kody’s family has chosen to remain optimistic. Their prayer, Jolynn said, is that Kody can live a normal life without needing a liver transplant.

For families in similar situations, her advice is straightforward: “Have faith in the doctors and in the treatment and in you as a parent—and stay strong.”

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

Indeed you are strong!

All if you Kody and Mom and Dad