Wearing stature-shadowing shoulder pads and a white and blue uniform, a boy rumbles across the practice field, blocking an imaginary opponent.

“Drive, drive, drive, drive,” his coach barks. “Drive to the whistle.”

Noah Kegeler, No. 30, knows about finishing off an opponent. He fought a tougher foe than most boys his age will face in a lifetime—Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome, a serious and sometimes fatal heart condition that occurs in less than 0.3 percent of the population.

“It’s a rapid heart rate that caused him to tire fast,” said Noah’s mom, Vanessa. “We discovered it while I was in labor. He had a heart rate around 300, with a high of 320 when I was in labor.”

Little Noah took medications for the first eight years of his life.

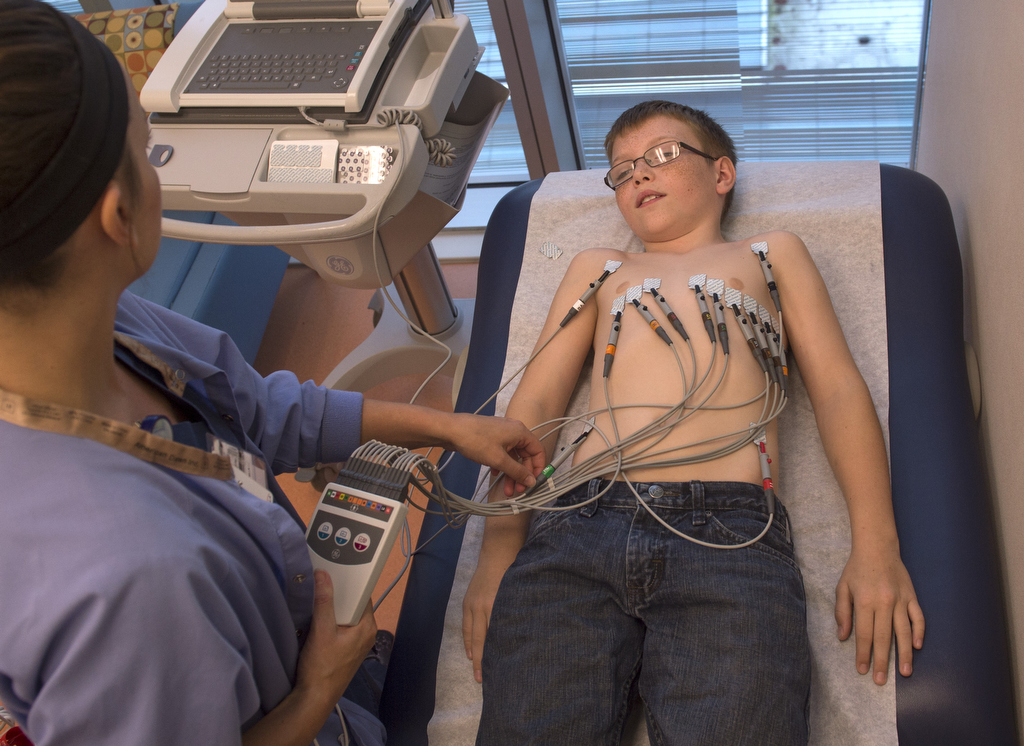

Last May, Spectrum Health Helen DeVos Children’s Hospital pediatric cardiologist Christopher Ratnasamy, MD, who specializes in electrophysiology, performed a cardiac ablation.

Now, instead of downing pills, the Jamestown Elementary fourth-grader downs footballs.

After years of watching patiently from the sideline, wondering when, or if he would ever play, Noah actualized a dream the moment he first stepped onto the football field this summer.

“We didn’t have him playing sports until after the ablation because we didn’t want to chance it,” Vanessa said. “He tired sooner than other children and there was a risk of getting his heart rate up higher than what his body could handle. There could have been something like a heart attack.”

Born with an extra connection between the upper and lower heart chambers, Noah’s heart raced up to 250-280 beats per minute, which could lead to cardiac arrest. A normal heart rate for a kid his age is closer to 100.

Dr. Ratnasamy treated Noah with the catheter ablation, a minimally invasive outpatient procedure.

“We advance the catheter from the vein in the leg and reach the heart,” Dr. Ratnasamy explained. “In Noah, the extra connection was on the left side.”

With the help of 3-D mapping technology, the doctor advanced the catheter to the left side of Noah’s heart, creating a tiny communication between the two upper chambers.

Noah recovered in less than a week. The procedure appears to be a game-changer.

“I believe he is cured of this condition,” Dr. Ratnasamy said.

“It was awesome being able to watch his first football game because of so many years of not knowing if he was ever going to be able to play football like the other kids,” Vanessa said. “I asked him after the game how he was feeling, how is your heart, is it beating normal?”

Moms worry. It’s part of the overall game plan.

At this recent practice, Noah drove hard, sweating, and reveling in every moment of the exertion. He powered into blocking pads. He ran a pass route. He cheered with his teammates.

“I love it,” the freckle-faced Noah said, taking a quick water break and wiping sweat from beneath his rectangular glasses.

Noah’s stepfather, James, said Noah is an inspiration.

“It’s absolutely amazing,” James said. “He had so much potential, but before he would have trouble breathing. I’m so pumped up to watch him. It’s like I’m out there with him. I get to see him living his dream.”

Noah may only be getting his cleats wet. His dreams run deeper, and wider.

“I want to play for a long time,” Noah said. “I want to play for the Lions.”

What position?

“Quarterback or running back,” the fourth-grader said in an all-things-are-possible-and-don’t-you-ever-doubt-it tone.

James believes in No. 30.

“He’s an amazing, amazing little boy,” James said. “Before, he couldn’t do much. To see him now, he’s a completely different person.”

As James spoke, the boisterous coach rallied the team.

“Hit them, drive them off the line or you will lose again,” Coach shouted to the pint-sized players, reflecting on a 33-13 dinger the night before.

But, fortunately, in the game that truly matters, Noah came out on top. Final score: Noah Kegeler, 1; Wolff-Parkinson-White, 0.

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>