When Dave and Jennifer DeSander learned their two children had hearing problems, one big thing worked to their advantage: timing.

The DeSander children—Cameron, 3, and Charlotte, 6 months old—were automatically screened right after birth, leading to quick detection.

“It seems like they have a good system in place,” he said. “The first time it was new to us, but we were kind of prepared the second time for it.”

Doctors installed a cochlear implant in Cameron, and outfitted Charlotte with a hearing aid. Charlotte will likely receive an implant at some point, but she’ll have to wait until she’s at least 1.

Robert Daniels, MD, an ear, nose and throat specialist at Spectrum Health, placed the cochlear implant in Cameron.

“He was phenomenal, and I really like him,” Dave said.

So when Charlotte’s diagnosis came around, her parents were prepared for the road ahead.

“We knew what to expect,” Dave said.

The treatment process for both children has been almost identical.

Doctors are unsure why both children have hearing loss, but they have indicated it may be hereditary. He and his wife are now undergoing genetic testing.

A different story

It’s difficult enough for parents when they learn their newborn has a hearing problem.

But when they don’t learn about the problem until much later—when the youngster is 2 or 3 years old, for instance—it makes the discovery that much more challenging.

While hospitals throughout Michigan are now required to screen newborns for hearing problems, it hasn’t always been so.

Just 20 years ago, there was no such requirement.

As a result, many parents were sent home with children who they assumed were perfectly healthy. Not until several years later did these parents realize their children had hearing problems.

That’s what happened to David and Nancy Cluley and their daughter, Hannah.

The Cluleys, of Grand Rapids, had two children before Hannah, and neither of the older siblings had hearing problems.

When Hannah was born, doctors didn’t order any special tests.

Hannah seemed to progress just fine as the months and years passed. She went to daycare, where she fit in beautifully. (Not until much later, after they learned about Hannah’s hearing problems, did David and Nancy discover that their ever-resourceful daughter had taught herself to read lips.)

Their first real hint of a problem came when Hannah reached 3 years old. Her grandmother noticed the youngster “speaking funny.”

“Dave and I had gotten used to (her speech) and so we didn’t recognize it as a problem,” Nancy said.

The grandmother’s discovery was the first step in a long and often difficult road for Hannah and her parents.

The Cluleys took Hannah to her pediatrician, who conducted three separate tests over time, none of which indicated Hannah had a hearing problem. The stumped pediatrician referred the child to an otolaryngologist in Grand Rapids who diagnosed Hannah with mild to moderate hearing loss. He then referred her to Butterworth Hospital, now part of the Spectrum Health system, for further testing.

A Diagnostic Brainstem Auditory Response test was performed to see if the hearing loss had an anatomical cause. It showed no apparent problems with the anatomy of her ears. After ruling out any possible genetic reasons, doctors deemed the problem idiopathic—in other words, “cause unknown.”

Late diagnosis

Hannah was immediately fitted for hearing aids, which have since been replaced about every five years. They did the job over the years, although if her hearing deteriorates further she may be a candidate for a cochlear implant.

While the hearing aids improved Hannah’s ability to hear, she still had to work hard to catch up to classmates in speech and language development, Nancy said.

Upon Hannah’s diagnosis, her parents enrolled her in a program for the oral deaf, which provided intensive language development training. Two years later she was mainstreamed into kindergarten so she didn’t miss any regular school, Nancy said.

During her first two years of school, Hannah also used an electronic box to help her hear teachers, although by second grade she stopped using this and, from that point on, relied only on hearing aids.

Nancy quickly came to realize what an important role hearing plays in the first few years of a child’s development.

“It would have been so much better had we discovered the hearing loss when she was born,” Nancy said. “I think we would have had her in a deaf program right from birth.”

Had the hearing loss been discovered at birth, it probably wouldn’t have been so emotionally draining, Nancy said.

Hannah, now 20, is doing well. Her hearing loss hasn’t worsened appreciably since her initial diagnosis.

“I feel very good knowing there are experts in the area that can help us if we have to go down the path of cochlear implants,” Nancy said.

Making changes

The Cluleys are a classic example of what happened to some families before newborn hearing tests became routine.

“One of the biggest things that has made diagnosing better is to provide infant screening,” said Kirsten Kramer, AuD, a clinical audiologist for Spectrum Health Helen DeVos Children’s Hospital. “Every baby born in Michigan gets a hearing test before they go home from the hospital.”

Dr. Kramer said while Michigan officials made newborn hearing tests mandatory in hospitals throughout the state in the early 2000s, Spectrum Health had already been conducting hearing tests for all newborns for years.

“The outcomes for kids with hearing loss have been much better because we’re enrolling them earlier and they are developing language skills despite the hearing loss,” Dr. Kramer said.

Twenty years ago, before the state began requiring hearing screenings across the board, about 50 percent of newborns with hearing problems actually showed no risk factors at birth, she said. As a result, the infants may have been sent home, where they likely went undiagnosed for years.

Newborns have a greater risk of developing hearing problems if their mother had an in-utero infection, if they have a family history of hearing loss, are placed in a neonatal intensive care unit for more than five days, or if they have a syndrome such as neurofibromatosis, Usher syndrome, Hunter syndrome, Friedreich ataxia or Charcot-Marie-Tooth.

Despite the extensive list of risk factors, only screening can detect hearing loss.

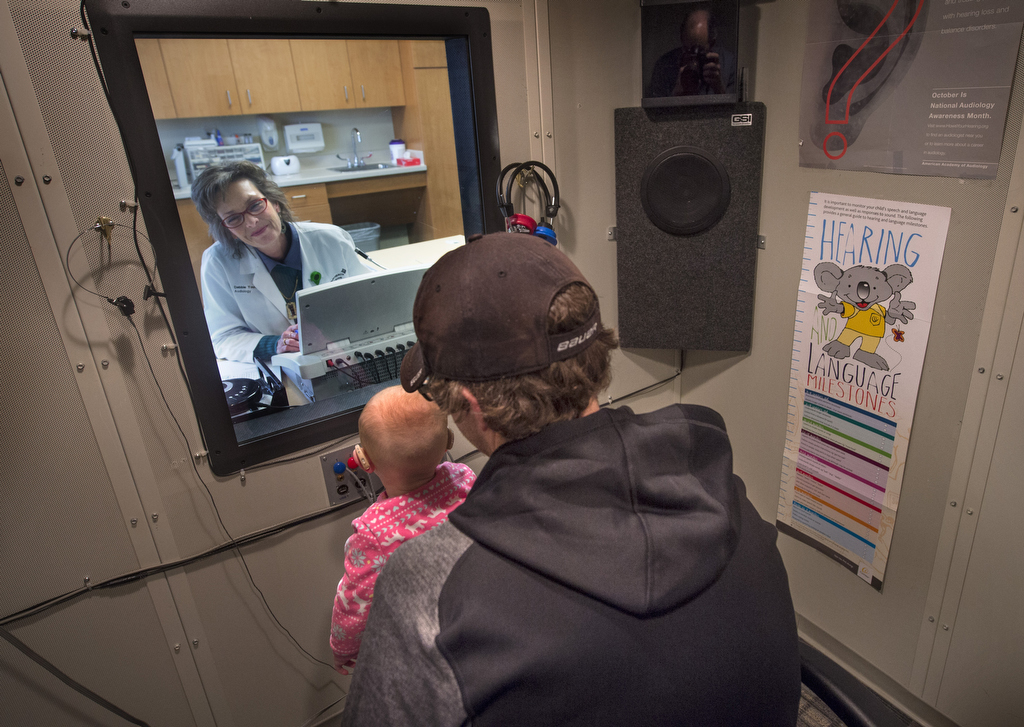

At Spectrum Health, an audiologist such as Dr. Kramer will diagnose and identify an infant’s hearing problem and then refer the family to an audiologist such as Debra Youngsma, AuD, CCC-A, at the Spectrum Health Medical Group Hearing Center.

Dr. Youngsma talks to parents about their treatment options, and about programs that can help cover expenses, such as Early On Michigan, a state-funded program that provides early intervention services to help children, birth to age 3, who have developmental delays or disabilities.

“Today, kids (with hearing loss) have a much better chance to develop normal language skills than they did 20 or more years ago because of the infant screening,” Dr. Youngsma said.

The treatment path, meanwhile, ultimately depends upon the child’s needs.

“Everyone is different,” Dr. Youngsma said.

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>