When someone with COVID-19 graduates from the intensive care unit, a celebration erupts.

Nurses, doctors, respiratory therapists and nurse techs cheer, clap and play their victory song as the patient is wheeled down the hall.

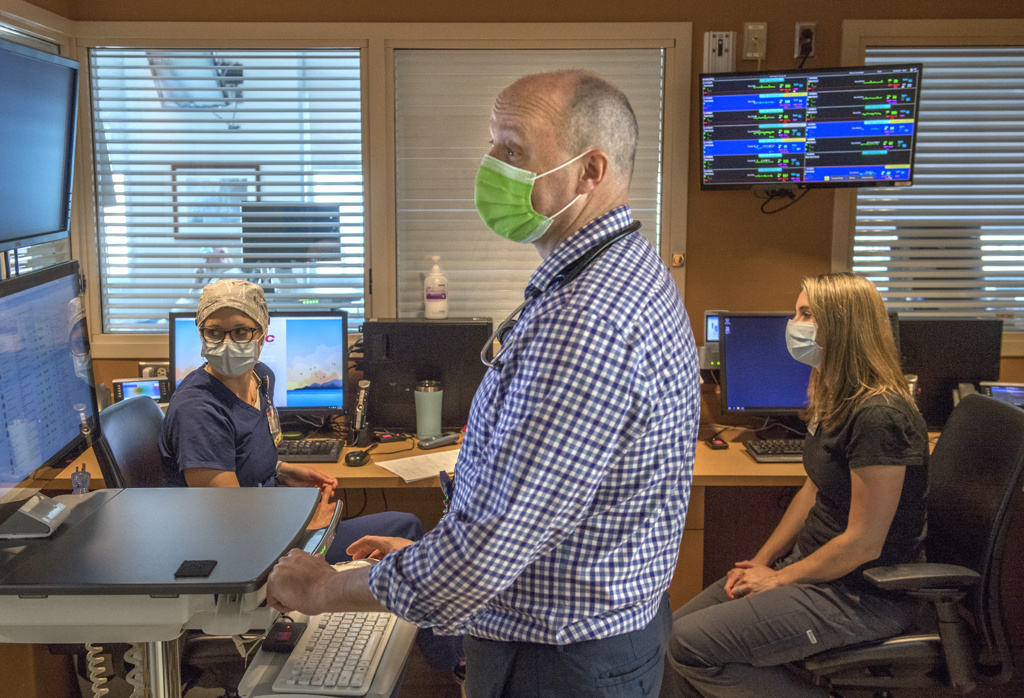

The team that cares for the most critically ill patients in the ICU at Spectrum Health Butterworth Hospital draws strength from those successes as they continue the challenging work of caring for those ill with the new coronavirus.

“Even though we are cheering on the patients, that excitement and joy is also for us,” said Patti DeLine, the nurse manager of the ICU designated to care for COVID-19 patients. “We are celebrating what has come to fruition and all the hard work our team has put into getting that patient healthy again.”

It’s a tough job—caring for patients as they fight life-and-death battles against a new disease that has swept across the globe in just months after it was identified. Not everyone survives. The medical team mourns each death.

And that’s one more reason why each victory, each recovery and graduation from the ICU, feels so rewarding.

Since the first COVID-19 patient arrived in the Butterworth Hospital ICU, the medical team has seen more than 100 patients graduate from the unit.

They have removed patients from ventilators—and watched as the patients once again breathed on their own.

“When we have these COVID-19 wins, you can see them beaming with pride,” DeLine said. “They were able to make that happen.”

Helping patients heal from this new coronavirus taps the team’s mental, physical and emotional resources. They research new developments while drawing on skills and knowledge gained treating other illnesses.

By the time the first patients with COVID-19 arrived at Butterworth Hospital, the medical team had followed developments in other areas—Italy, New York and Detroit—where surges in patients stretched the capacities of medical systems.

“Obviously, you learn from those who are ahead of us on the road in terms of what works and what doesn’t work,” said pulmonologist Stephen Fitch, MD.

“The longer you go into this, the more you learn, the more information you have—and that informs your care and what you are doing.”

Ventilator support

Although the novel coronavirus was just identified in late 2019, physicians can apply what they know from treating other patients with other illnesses, including influenza, the H1N1 flu, and the viruses that cause SARS and MERS.

Most of the patients have severe inflammation in the lungs, either from pneumonia or the inflammatory response caused by acute respiratory distress syndrome. The lungs, unable to do their job of exchanging oxygen with carbon dioxide, send less oxygen into the bloodstream—and to the organs that require it.

Doctors deliver supplemental oxygen through a nasal canula—or a high-flow nasal canula, if needed.

“If that’s insufficient, you have to use a ventilator,” Dr. Fitch said.

Patients typically are sedated as they are intubated, and the ventilator begins to deliver oxygen into the lungs.

This helps patients get needed oxygen, while also relieving them of the work involved in breathing. When oxygen is in short supply, breathing taxes the respiratory muscles—and that in turn increases the need for oxygen.

Not all ICU patients with COVID-19 require ventilator support. Those who do spend an average of 10½ days on the ventilator.

During that time, the medical team carefully monitors the patient’s oxygen level and the condition of the lungs, adjusting ventilator pressures to optimize lung function.

“As those mechanics get better and the blood parameters get better, we are continually working to wean that level of support and the level of sedation,” Dr. Fitch said.

Also as part of standard ICU care, the team provides nutritional support, occupational and physical therapy.

“These are supportive therapies, not cures,” Dr. Fitch said. “They don’t make the virus go away. But they are all treatments that we know from scientific study improve patient’s survival and help them recover and get back to baseline.”

The team also puts patients in a prone position—turning them on their stomachs—often for 12-16 hours a day. This relieves pressure on the lungs and opens airways.

Other treatments include plasma therapy using plasma donated by those who have antibodies to the COVID-19 virus. Patients may also receive anti-inflammatory medications and antiviral drugs, such as Remdesivir, which was developed to treat the Ebola virus.

Th medical team continues to study reports from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and other health systems, as well as evaluating its own practices, as it works to provide the best treatments for the patients.

“We are certainly encouraged by the positive outcomes we have seen in our health system,” Dr. Fitch said. “We have to figure out what things we are doing that we can attribute that to.”

Tilting beds

Dr. Fitch credited nurse Michelle Rowland with leading the way on one change in practice.

Rowland took care of a man whom she believed would benefit from proning—being turned on his stomach.

She requested an order from a physician and a team to help turn over the patient—it takes four or five nurses and nurses techs, plus a respiratory therapist to move a critically ill patient from his back to his stomach.

While waiting for everything to fall into place, she realized she could take an interim step. The ICU beds include a “lateral rotation” feature, which slowly rocks the bed from side to side.

Although designed to prevent bed sores, Rowland thought it might help patients with fluid in their lungs.

“When those lungs get that sick, they get like soggy sponges,” she said. “We know that moving them frequently helps.”

She turned on the lateral rotation. Like a slow-moving cradle, the bed rocked slowly back and forth, changing positions every 10 minutes. It tilted one side up 20 degrees, then returned to a flat position, then tilted the other side up 20 degrees.

She soon saw results—a steady improvement in the man’s oxygen levels.

DeLine wasn’t surprised by Rowland’s ingenuity when she learned what she had done.

“She is very creative. She is always thinking ahead,” DeLine said. “She is a fantastic nurse.”

She and Rowland discussed the approach with a clinical research nurse and Dr. Fitch.

“Now we turn it on with nearly every single COVID-19 patient,” DeLine said.

It’s hard to tell how much it affects a patient’s recovery—amid the many other therapies provided. But DeLine believes it may help by shifting fluid off areas of the lungs, allowing them to work better.

That kind of out-of-the-box thinking is common among those drawn to work in the medical ICU.

“Dr. Fitch is leading this team in a way that is curious and collaborative,” DeLine said. “We all work together. That makes a huge difference when you have people who are willing to step up and do what is right for each patient.”

Giving extra love

Keenly aware that patients are separated from their loved ones, the nurses do all they can to bring a sense of human connection.

“We are acutely aware that they don’t have the love of their family there, so we are giving them extra love to make up for it,” DeLine said. “Even though we are in gowns and gloves, that doesn’t change the fact that we love what we do.”

The nurses arrange video calls for patients and family members. And they call loved ones to let them know about big and small milestones.

“We will call sometimes just to say he opened his eyes. He squeezed my hand today,’” DeLine said. “If my family member were here, I would want to know there is someone in there holding their hand, wiping their tears and smiling at them when they wake up.”

Just as the medical team celebrates patient’s victories, they take it to heart when a patient dies.

While many COVID-19 patients have recovered enough to leave the Butterworth Hospital ICU, some have died. The nurses and therapists who care for them grieve for the patients and their loved ones.

“It is heartbreaking,” DeLine said. “The nurses look at them like that’s their grandpa, that’s their dad. You can’t help but see the people you love in the people you are caring for.

“There are a lot of things that are difficult for the nursing staff. We talk a lot about coping skills, about recognizing burnout and stress.”

The team also has access to services Spectrum Health offers employees to help cope with stress, including counseling, spiritual support, yoga classes and a meditation app.

That dedication, combined with skills and experience in ICU care, are key elements in patients’ recovery, Dr. Fitch said.

“It’s just astonishing to me—the persistent, steady effective work that people do every day to take care of these patients,” he said. “That is one of the central pieces: good solid training on how to take care of sick patients and attention to details.

“Doing that over and over again, day after day, is what wins the day.”

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>