Just 11 days after his right leg was amputated below the knee, Troy Hodge walked again.

Up on two feet—with help from a custom-fit early post-operative prosthetic device—he took several steps.

This early prosthesis isn’t his permanent prosthetic device, but it’s helping him get through the transition until his residual limb has healed well enough to take a standard prosthesis—likely in April.

And when Hodge, 55, returns from Michigan to his home state of West Virginia, the device will allow him to climb the 13 stairs to the door of his girlfriend’s condo.

“It helps me get around better,” Hodge said, as he prepared to leave the Inpatient Rehabilitation Center at Spectrum Health Blodgett Hospital in February. “I don’t have to hop everywhere. And I don’t have to have a wheelchair.”

Early independence

The early prosthesis works by grabbing hold of the leg above the incision site and distributing the pressure around the perimeter of the limb, rather than putting direct pressure on the incision. Hodge’s device was fabricated by Hanger Clinic, Spectrum Health’s orthotics and prosthetics provider.

Not every amputee is a good candidate for an early prosthesis. The device comes with some risks, and if it’s not used properly, it can make matters much worse.

“Typically, amputees do not receive a prosthetic device until after their incision has completely healed, which can be two to three months down the road,” said Jamie DuVerneay, CTRS, the program coordinator at the inpatient rehab center. But for those who qualify, an early device gives patients more independence “and actually improves circulation to promote healing.”

Hodge fit the criteria for the device perfectly. Despite having diabetes, he is in good overall health and has excellent upper body strength—a must for someone learning to walk with a prosthesis.

His circulation and healing potential are also good, thanks to a vascular bypass performed before his amputation by Peter Wong, MD, a vascular surgeon with Spectrum Health Medical Group.

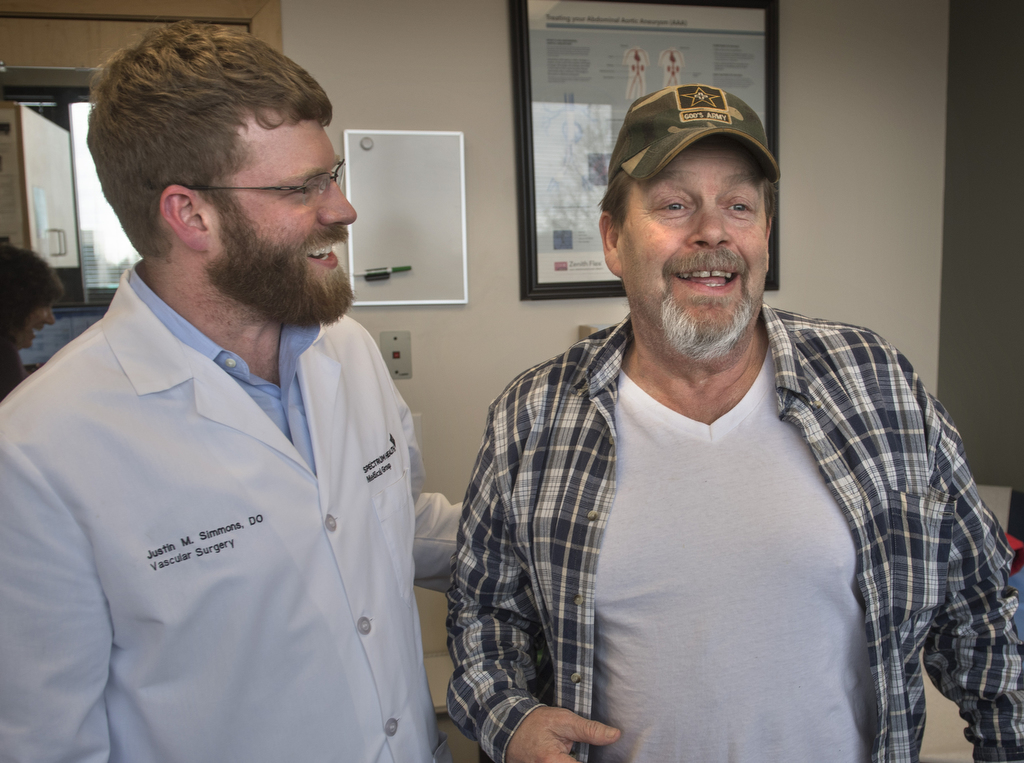

All of these factors convinced his primary vascular surgeon, Justin Simmons, DO, also of Spectrum Health Medical Group, to give the green light for the early prosthesis.

Perhaps most important for Hodge’s success, he has the motivation to succeed.

“When I first started, I said, ‘I’m not going to go up there and lay around.’ I said, ‘I’m going to get things done so I can get out of there and get home,’” Hodge said.

Peripheral arterial disease

These days, home for Hodge is split between West Michigan and West Virginia. He left West Virginia last August when—after undergoing 15 procedures in the space of five months to remove blood clots and treat blockages in his right leg—he experienced severe pain and finally lost faith his doctors there could help him.

Barely able to use his leg, Hodge packed his car and drove to Remus, Michigan, to stay with relatives. He hoped to find a medical team that could restore his leg or at least relieve the constant pain.

By October, he had an appointment with Dr. Simmons, who diagnosed peripheral arterial disease, a narrowing of the arteries caused by a buildup of plaque. This plaque buildup is known as atherosclerosis, or hardening of the arteries.

Nicotine use and diabetes are the top two risk factors for peripheral arterial disease, and Hodge had both, Dr. Simmons said.

“He was a diabetic and he was still a smoker—although he was trying to cut back and was making headway,” the doctor said. “Nobody really understands … if it’s got nicotine in it, it’s going to wreak havoc on those arteries.”

In Hodge’s case, the blood flow down into his leg became so poor that Dr. Simmons classified it as critical limb ischemia. People at this stage experience constant pain in the lower extremities.

He wasn’t sure he could eliminate Hodge’s pain, but he knew he had to try. The hope was that by restoring blood flow into his foot, he could get the leg functioning and feeling normal again.

He admitted Hodge to Spectrum Health Butterworth Hospital, did an angiogram to get a better picture of the problem and scheduled his colleague Dr. Wong to perform a peripheral artery bypass.

The bypass worked beautifully, but when Dr. Simmons saw Hodge after surgery, the pain still hadn’t subsided.

The culprit? Nerve damage.

“The nerves have gone without blood for so long, and it just doesn’t ever recover, even once you restore blood flow,” Dr. Simmons said.

The next possible solution was pain management. Fearing addiction, Hodge expressed his reluctance to take narcotics, so Dr. Simmons looked for alternative treatments.

“What I wanted to do with Troy is get him into a pain management clinic to see if we could work on isolating out the nerve, treating that nerve, things like that. But he couldn’t get in for months,” Dr. Simmons said. Because of the opioid crisis, pain management clinics today are “drowning in referrals and in patients.”

Hodge felt stuck in an unbearable situation with no relief in sight.

“I mean, it hurt 24 hours a day, 7 days a week,” he said.

Last resort

By November, Hodge chose the solution he and Dr. Simmons considered their last resort: amputation.

There are only two reasons for taking a patient’s limb, Dr. Simmons explained—uncontrollable pain or uncontrollable, life-threatening infection. He hates having to do it “with an absolute passion,” he said, but sometimes it’s the best option.

“What I tell people as I’m having the amputation discussion is, ‘Yeah, short term it sucks. We’ve gotten to this point. Nobody likes it. I don’t like doing it, you don’t like the fact that you’re losing your leg. I get it. But long term your quality of life is going to be much better.’”

Thankfully, with good blood flow established in Hodge’s leg, Dr. Simmons could do a below-knee amputation. For patients with good healing potential, this is better than an above-knee amputation because it improves their odds of walking with a prosthesis.

“We always try below-knee amputation, even if there’s a potential that’s it’s going to fail, because that’s the best opportunity the person’s going to have to get around with a prosthetic,” he said. “About 75 percent of those people will walk.”

Back to living

On a snowy Friday in February, Hodge put on his temporary prosthesis and walked out of the rehab facility on his own, with a single crutch for support.

Having practiced walking and climbing stairs for more than a week with physical therapists, he was ready to carry on at his cousin’s house, doing prescribed exercises and using his prosthetic device three times a day, for two hours at a time.

“I’m pretty well used to it now, but it’s still going to take time really to get moving in it because I’m new at it. But it’s working out great,” he said. “I feel good.”

Hodge has his next steps carefully planned out: Return to Dr. Simmons in early March to have the staples removed from his incision; visit the Blodgett Hospital amputee clinic to follow up with his physiatrist, Dennis Suzara, DO, and his prosthetist from Hanger Clinic; then return to West Virginia to get his life back on track.

“I want to go back to work doing something—selling car parts or something,” said Hodge, who worked as an auto mechanic for 28 years.

He won’t be in West Virginia for good, though. He plans to return to Spectrum Health for scheduled follow-ups, and he’d like to move to Michigan once he’s made the transition to a permanent prosthesis.

Dr. Simmons thinks his future looks bright.

“He’s got a good, positive outlook on things, which is a huge component in post-amputation rehab,” he said. “He’s going to get back to living his life.”

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>