But who’s counting?

3,676 days add up to a bit more than 10 years. It was a decade ago, in 2011, that Rick Eding, 46, had a device attached to his body that would help pump blood to his failing heart.

The LVAD, or left ventricular assist device, would save his life.

Eding’s journey began 21 years ago, when the Dorr, Michigan, resident first stumbled into an emergency room at Spectrum Health Zeeland Community Hospital with what he thought was a mean sinus infection.

An allergic reaction to antibiotics had blossomed into cardiac arrest.

Rushed to Spectrum Health Butterworth Hospital, Eding learned he had cardiomyopathy, a heart condition in which the heart lining becomes abnormally thick.

Eding recovered, but his heart problems proved to be far from over. For years, Eding struggled with shortness of breath and fatigue. He started making frequent visits to his doctor.

His ultimate diagnosis of heart failure made him a prime candidate for the LVAD.

Ten years later

In 2021, Eding sits on the examination table at the Spectrum Health Heart and Lung Transplant office at 330 Barclay Avenue NE in Grand Rapids, Michigan. He returns here every two to three months for a checkup.

He is surrounded by familiar faces—his wife, Kelly, three of the youngest of their six children, Jacquie Oliai, FNP, and Jessica Everly, clinical VAD coordinator.

The room resounds with laughter and chatter. That may not be typical for heart failure patients, but it is typical for Eding.

“He’s a trendsetter,” Oliai jokes, and Eding grins.

“Everything about me is unusual,” he echoes, mischief sparking in his eyes. His family immediately begins to tease him in long-practiced manner.

“Oh, he’s unusual, all right,” Oliai joins in, “and maybe even more so than he says. None of our patients have been on a VAD as long as Rick. And he’s been remarkably successful with it.”

Eding nods at the nurse practitioner.

“You were working in a broom closet 10 years ago,” he says to her. “When I first got the VAD, we had to do daily dressings, and it was a sticky mess. It took about 20 minutes, I needed Kelly’s help, and I had to cover a table with all the components of the dressing. Now I get a neat kit and change the dressing only once a week. I do it alone and it takes me six, maybe seven minutes.”

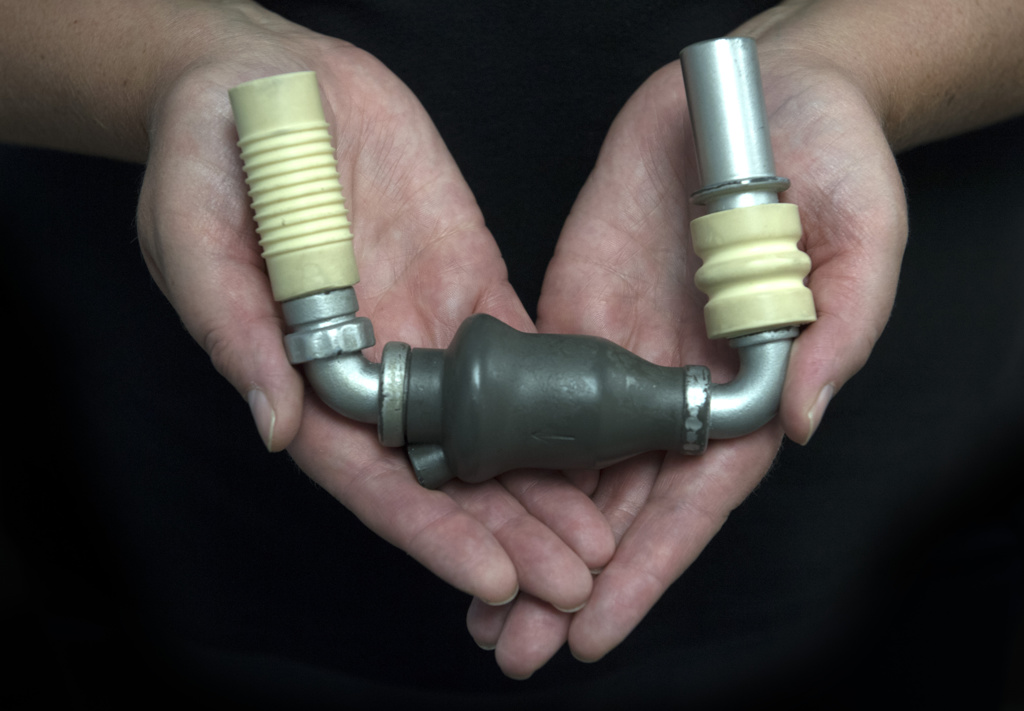

Eding lifts his shirt to show the device on his right side. A controller that is a bit larger than a cell phone is attached to his belt. It is connected to a small mechanical pump that surgeons placed near his heart. Eding also carries a small power source when he is mobile, or he can plug the device directly into a power source.

“Before I had the VAD, I was sleeping 16 to 18 hours a day,” Eding says. “I would fall asleep in the shower. Always tired. Couldn’t breathe. It all comes down to quality of life, and that’s what I’ve gotten back with this thing.”

Waiting on the wait list

Although Eding no longer works as an electrician, he remains busy as an active stay-at-home Dad who rarely stays at home long.

“I coach middle school football,” he says. “I’ve coached some of our own boys. And I fish—a lot—because it’s so therapeutic. I clean and cook the walleye myself. And I restore antique tractors.”

When Eding first received the LVAD, he aimed to get on the heart transplant wait list.

He soon found out his weight, which crept up to 330, had become a barrier to being a candidate for a donor heart.

“Again, trendsetter!” Oliai says. “Rick was our first LVAD patient to undergo bariatric surgery, and for that reason his surgery happened at the Meijer Heart Center so that we could monitor his heart during the surgery.”

After a successful sleeve gastrectomy, thanks to a unique partnership between Spectrum Health’s bariatric division, cardiothoracic division, and the advanced heart failure team, Eding soon began to lose weight.

“Right now, though, I’m taking a break,” Eding says. “I should lose another 50 pounds to become eligible for a heart transplant but being on a wait list comes with a lot of guidelines and requirements.”

Although the LVAD comes with some restrictions, such as keeping it away from water, Eding has adjusted to his life with the device and is comfortable using it for perhaps years into the future.

“We currently have 105 patients across Michigan using the VAD, from Indiana up to the Upper Peninsula,” says Everly, the VAD coordinator. “Even kids can use it. We have ages 18 into the 70s right now.”

“Lots of people ask me about it,” Eding adds. “I talk with other patients sometimes who are going through the same thing. Mostly they ask me—is the VAD worth it? Can I still drive? What about relations with my wife?”

Eding laughs, then says: “Yes, yes, and yes. It’s worth it if you care about the quality of life. (It) made a big difference in mine.”

Surprise!

Eding hops down from the exam table and follows his family out the door of the doctor’s office. Everly motions them in another direction, to the transplant office break room.

“Something I want to show you,” she says.

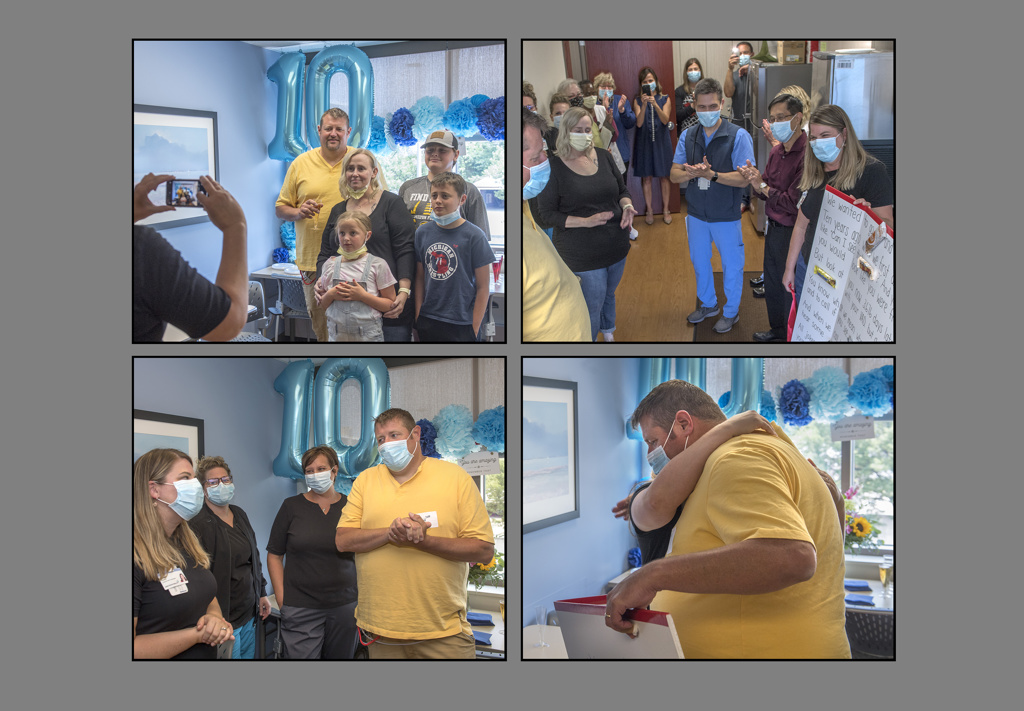

Eding enters the break room to resounding cheers. Balloons decorate the walls, a sign reads “10 YEARS,” another reads “YOU ARE AMAZING,” and a row of smiling faces line the walls—his health care team of the past 10 years is here to mark the milestone.

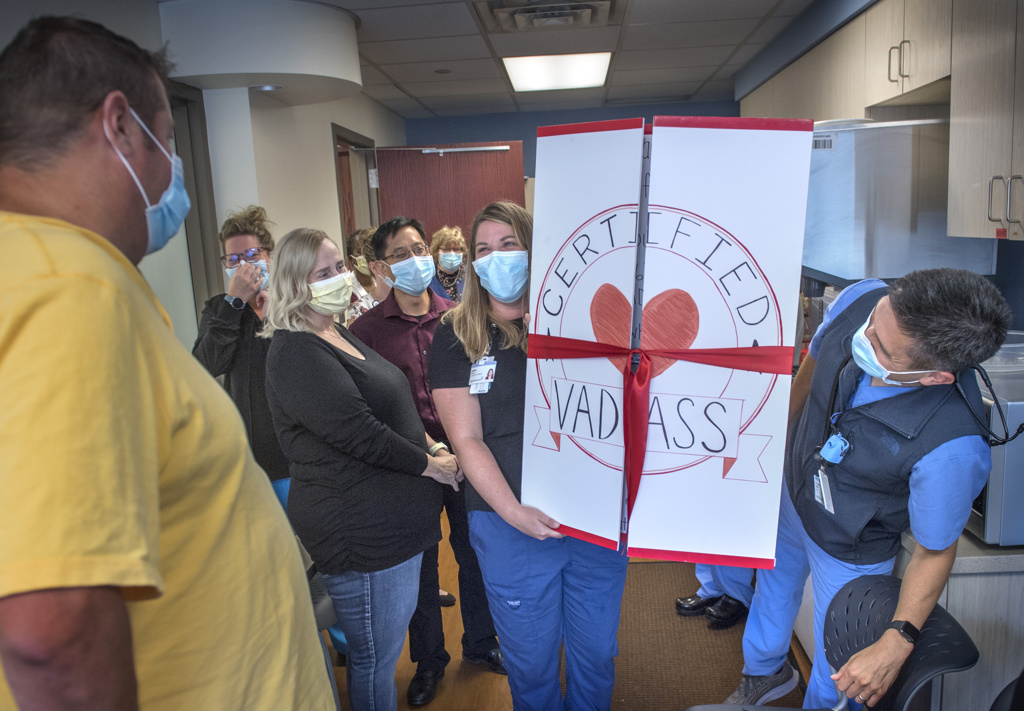

Someone brings in an immense cardboard card, almost as big as the recipient. Its cover announces: “Certified VAD ass.”

Eding chortles, blushes just a little, and takes it all in. These people—they have become his second family.

Sangjin Lee, MD, cardiologist and medical director, has kept a close eye on Eding’s heart since 2014. He lifts a glass to toast his patient.

“Ten years, that’s quite remarkable,” he says. “And Rick’s level of activity. This has all been a team effort, as you can see,” he indicates the room.

“We need to get the word out about the VAD, both to physicians and to patients. When your quality of life suffers, when you are going to the hospital too often, that’s when it is time to consider a VAD. You can see how it changes everything.”

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>