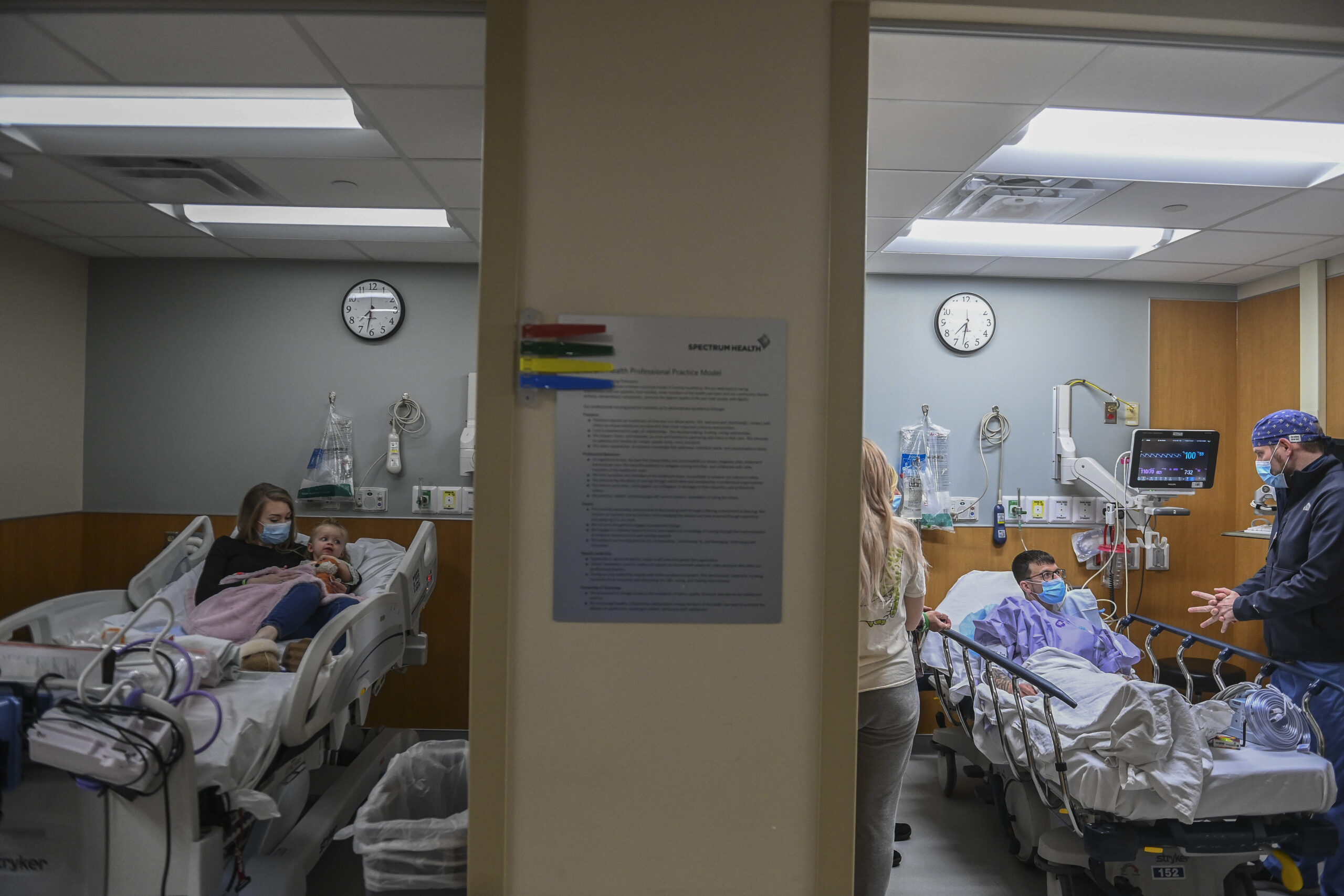

Cody Ireland sat up in his hospital bed and took his 2-year-daughter, Hudson, onto his lap.

Looking into her clear blue eyes, he said, “I’m going to save your life today.”

Hudson snuggled against him, oblivious to the activity that surrounded them as the medical team prepared for their surgeries.

That morning, Cody did indeed give a life-saving gift to his daughter—he donated his kidney to her in a transplant surgery at Corewell Health’s Butterworth Hospital.

For Cody, it was a gift just to be able to provide the kidney his daughter so desperately needed.

“I would do it a thousand times over,” he said.

‘An ultra-rare disease’

The transplant surgery marked a welcome turning point in Hudson’s struggle with an extremely rare and life-threatening kidney disease.

Her parents, Cody and Kendra Ireland, had no inkling that Hudson, their first child, had the condition when she was born two years ago at Corewell Health’s Zeeland Community Hospital.

Newborn screening tests showed she had hypothyroidism, caused by an under-functioning thyroid gland. She began to take tablets daily to provide thyroid hormone.

But otherwise, Hudson thrived for the first few months, a bubbly and happy baby.

Around 5 months, she developed a series of illnesses, including a case of bronchiolitis that lingered for several months, despite treatment.

Then she began to wake up with eyes so swollen that she could not see at first.

At 9 months, a blood test started Hudson on the path toward a diagnosis. When the test showed extremely low levels of protein, Hudson’s parents brought her to Corewell Health’s Helen DeVos Children’s Hospital.

After more tests, they learned the disease Hudson faced was far more serious than they imagined.

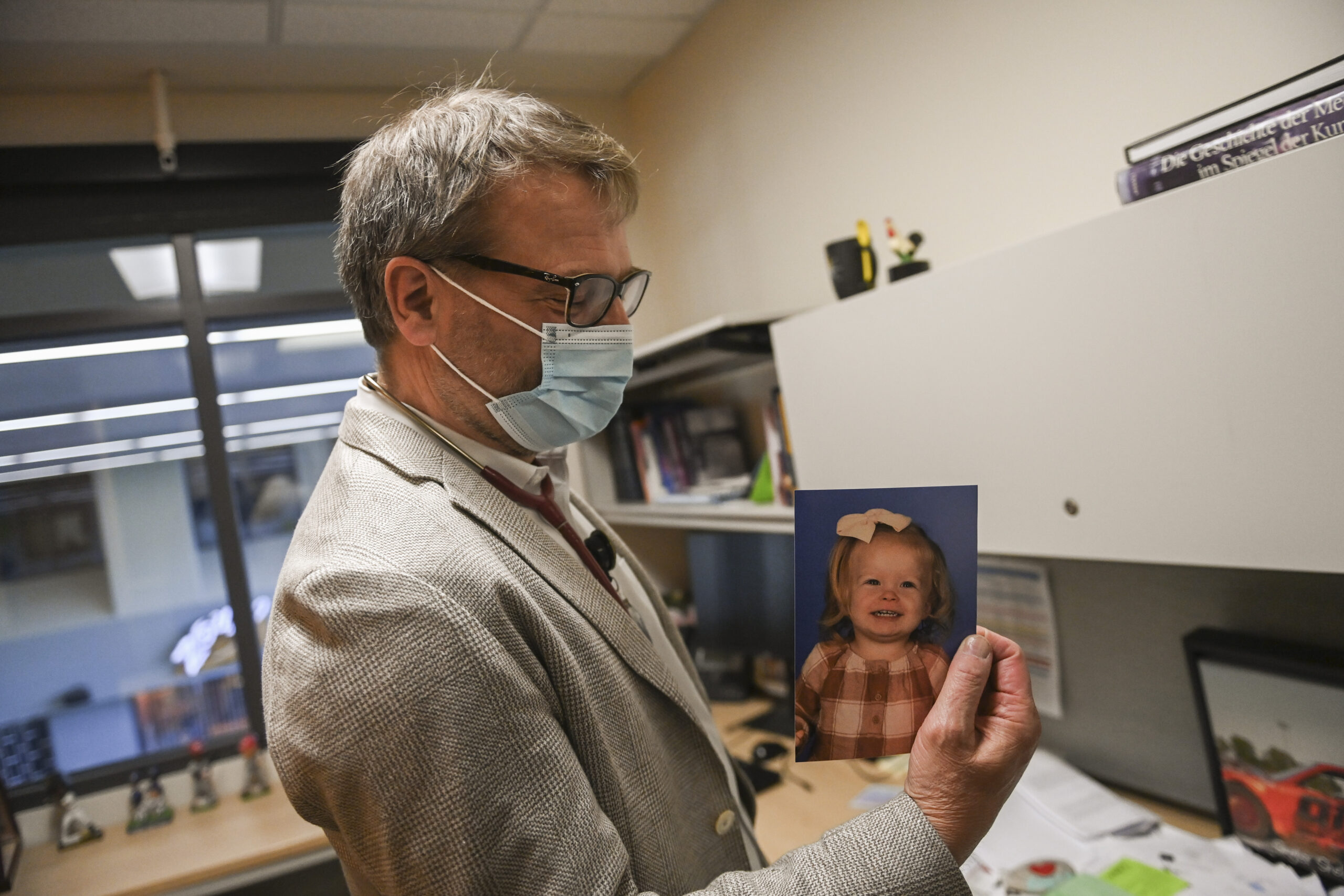

“She has an ultra-rare disease called congenital nephrotic syndrome,” Jens Goebel, MD, a pediatric nephrologist at Helen DeVos Children’s Hospital, said.

A genetic mutation impairs the function of the kidneys’ filters, causing an excessive loss of protein in the urine.

With low levels of protein in her blood, Hudson’s blood vessels leaked fluid, which caused swelling throughout her body. Her blood became thicker, raising her risk of blood clots.

As Kendra and Cody struggled to understand the diagnosis, one thing became painfully clear to them: “The only thing that was going to save her life was a kidney transplant,” Cody said.

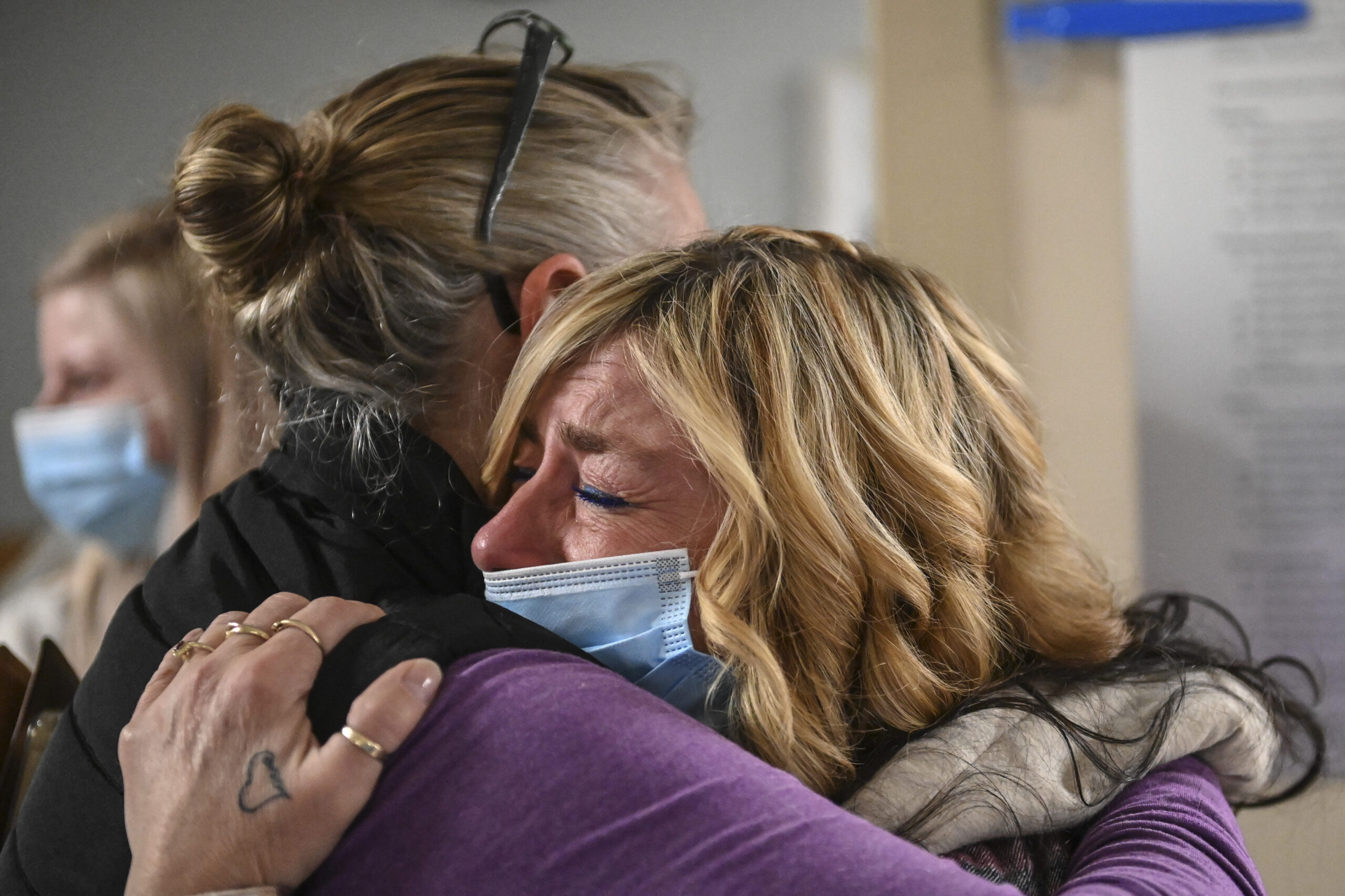

Stunned, the couple wept.

“There is so much emotion flooding in at one time. You kind of black out,” Cody said.

Working toward a transplant

The next step for Hudson’s parents and medical team: Help Hudson grow big enough to undergo transplant surgery.

For the next year, Hudson received weekly protein infusions. Her parents gave her twice-daily injections of blood thinner, as well as several other medications.

When she was 1 year old, Hudson had her left kidney removed to help reduce the loss of protein.

Nine months later, when she had become big enough to get transplanted, she had her right kidney kidney removed.

Watching Hudson recover from the second surgery was heartbreaking for her parents.

“For about three to four weeks, she didn’t want to eat,” Kendra said. “She didn’t want to talk. She didn’t walk. She just wanted to be held.”

Without kidneys, Hudson needed dialysis for several months until she was no longer nephrotic and thus safe to transplant. Cody and Kendra provided it at home every night, a 12-hour process while Hudson slept.

Both parents wanted to donate their kidney to Hudson.

Cody insisted that he go first because, at 32, he is a few years older than Kendra. He reasoned that if Hudson needed a second transplant in the future, Kendra would be more likely to qualify as a donor.

After a series of tests and interviews, the transplant coordinator called: Cody was approved as a donor.

“It was a huge weight off our shoulders,” he said. “We have watched this little girl fight for her life and do her best. We were so ready for her to have a shot at living a normal life.”

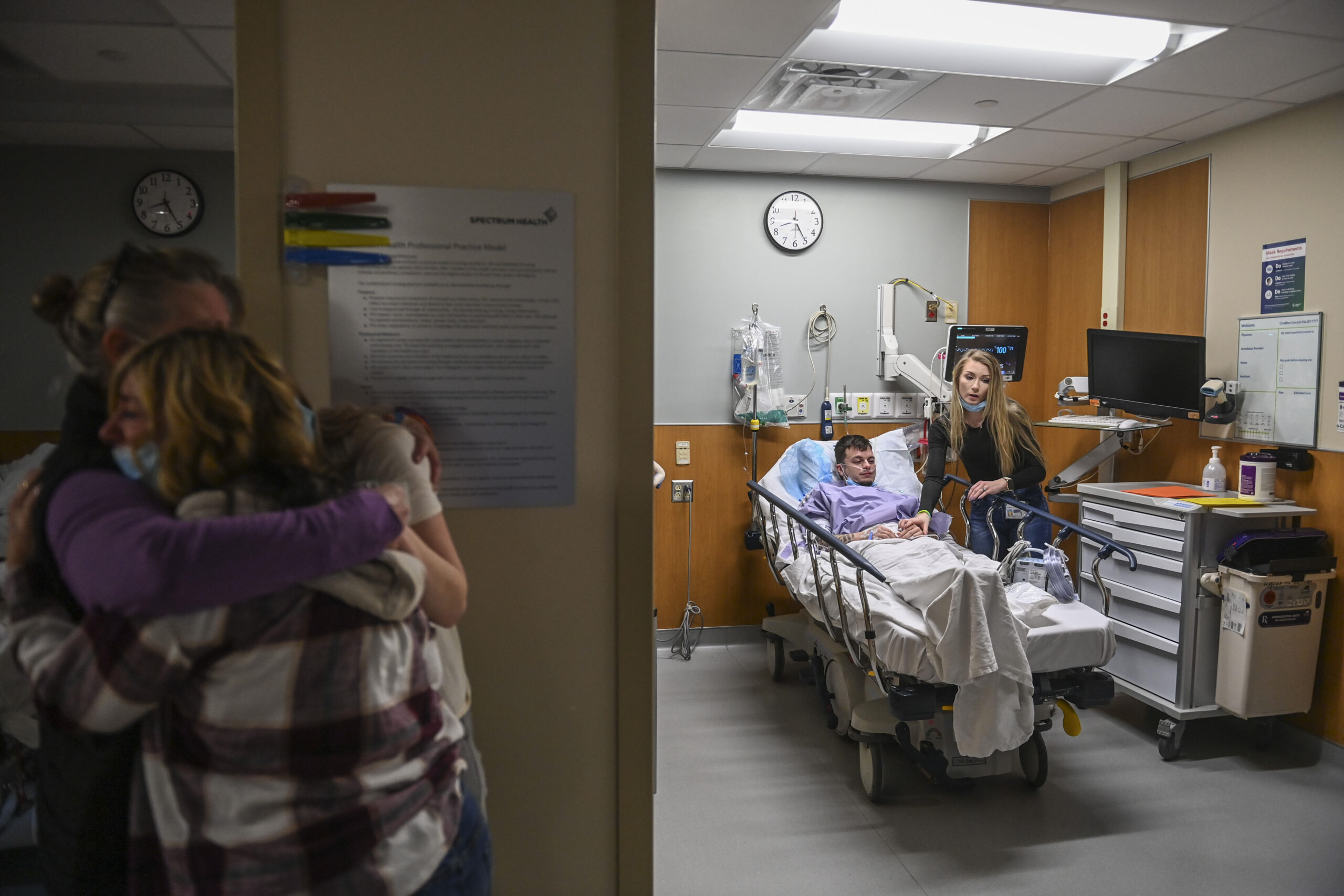

Ready for surgery

On the morning of the transplant, Cody made the most of his moments holding Hudson before going into surgery.

“No matter what happens, you are going to be wonderful. This is all going to be OK,” he told her.

“You deserve this, and you are going to grow up into a wonderful lady someday.”

Cody admitted he was terrified—but not for himself. He worried about how his tiny daughter would handle the operation.

Hudson weighed only 24 pounds.

“She is one of the smallest children (to receive a kidney transplant)—not just for Helen DeVos Children’s Hospital, but for any pediatric kidney transplant program,” Dr. Goebel said.

In the past, children had to weigh more to be considered for a kidney transplant. For young children with kidney disease and on dialysis, it could take take a couple of years to grow to the size required for a transplant.

“It’s not good for these kids to be on dialysis any longer than they have to,” Dr. Goebel said.

With advances in surgery and care post-transplant, doctors now can provide transplants to smaller children.

Hudson’s transplant surgery was unusual in another way—her kidneys were able to filter waste products from her body.

Congenital nephrotic syndrome “is the only disease that requires a kidney transplant despite the fact that kidney function is normal,” Dr. Goebel said. “It’s just that there is an astronomical protein loss, which is not healthy long-term.”

Adjoining operating rooms

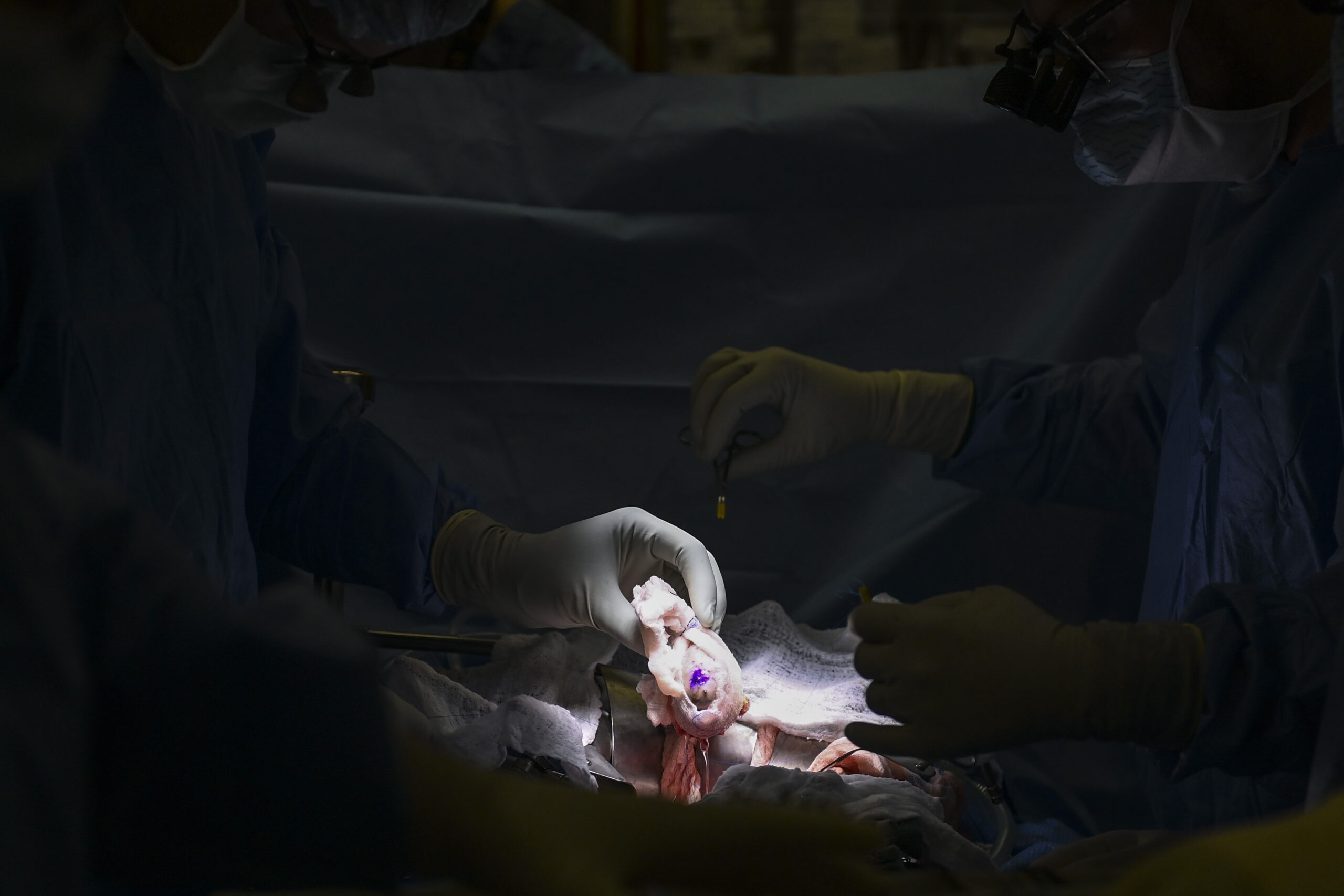

Cody and Hudson underwent surgery in adjoining operating rooms. Once the surgeon removed Cody’s kidney, it was carried through the door to Hudson’s room for transplant.

“There are more hands-on challenges related to a transplant involving an adult donor kidney,” Dr. Goebel said.

Rather than place the kidney in the groin, surgeons place it in the belly so they can connect it to the aorta and the inferior vena cava—the blood vessels large enough to supply and drain an adult-sized kidney.

“They have to make a bigger incision and flip the bowel out of the way,” Dr. Goebel said. “These kids require a few extra days of recovery time.”

In recovery, Hudson received a lot of fluids to provide enough blood volume for her new adult-sized kidney. Because of that she remained on a ventilator longer.

Three weeks after the transplant, Hudson was ready to go home.

“It worked out very well,” Dr. Goebel said.

Transformed with a new kidney

Hudson ran across her living room, her blond wavy hair flying, as she carried her toy fox and owl to visitors.

She climbed on a rocking unicorn and laughed as her dad rode a rocking whale beside her.

Kendra blew bubbles, and Hudson giggled and reached for them.

“Pop, pop, pop,” she said. “Uh-oh!”

Five weeks post-transplant, Kendra and Cody marveled at their daughter’s transformation.

Always easygoing and happy, Hudson became a whirling bundle of energy and joy once she had a healthy kidney.

“It’s like we brought a whole different kid home from the hospital,” Kendra said. “As soon as she got home, she wanted to do nothing but play from morning to night.”

As the donor, Cody endured pain, intense cramps and fatigue the first few weeks after surgery.

“I think the month of semi-struggle I had is totally worth it—for her to be healthy,” he said.

Looking ahead with hope

The future looks bright for Hudson, Dr. Goebel said.

She will always need anti-rejection medicine and regular visits with her doctor to monitor her kidney function.

“Beyond that, she is going to live pretty darn close to normal,” he said. “She can go to school, play soccer, get married, have babies.”

Having a living donor—and one who is a parent—increases the likelihood of her kidney lasting a long time, he said. So does the dedication of her parents, who make sure she gets the medication and care she needs.

How long will the kidney last for Hudson? Maybe 20 to 30 years, Dr. Goebel said. But it is hard to predict the medical advances that will emerge over time—and potentially improve her options in the future.

‘So nice having her home’

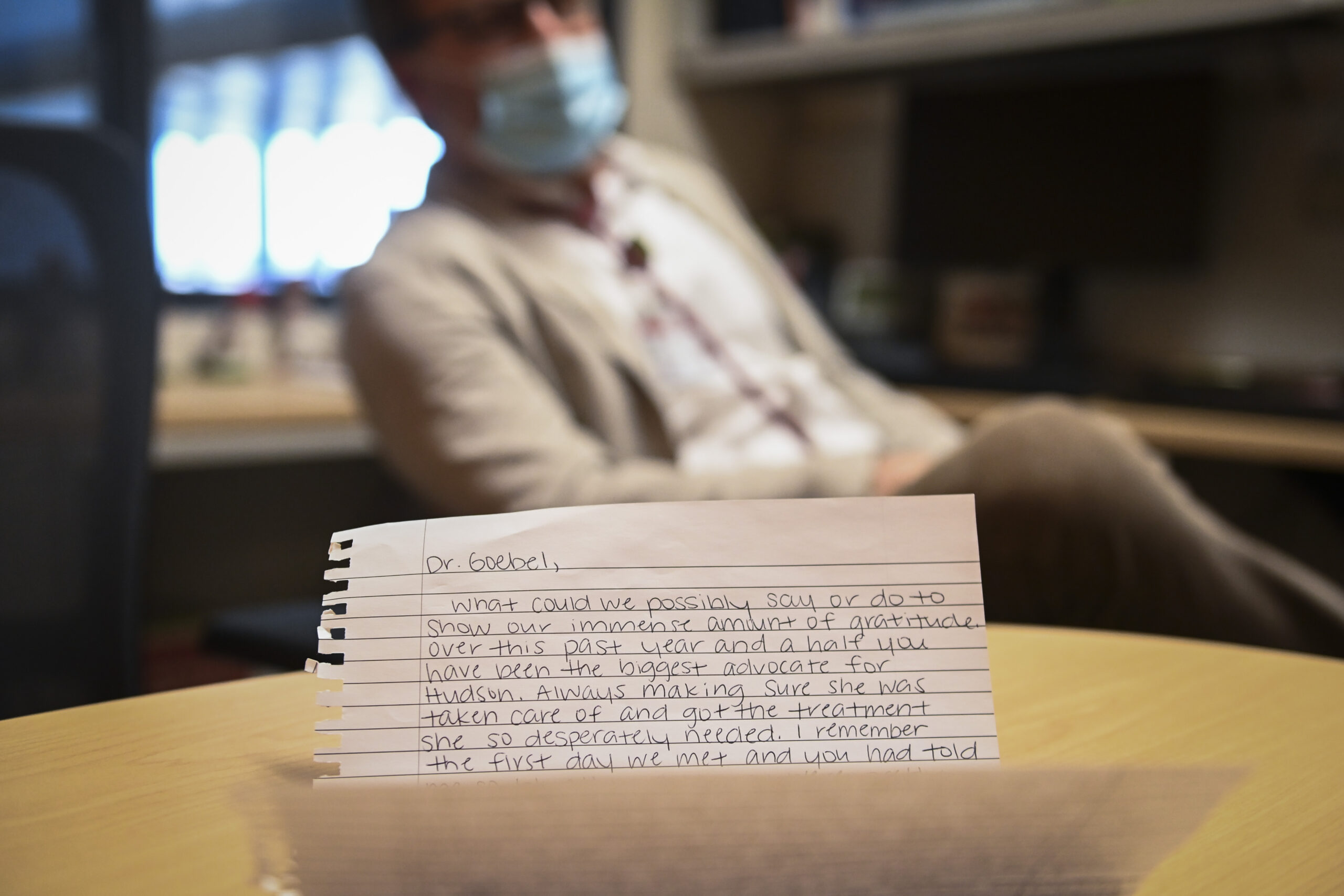

Seven weeks after receiving her new kidney, Hudson and her parents visited Dr. Goebel at Helen DeVos Children Hospital’s pediatric nephrology clinic.

“Miss Hudson, can I listen to your heart?” Dr. Goebel asked.

He gave her a turn with the stethoscope, and she placed it on her dad’s chest, saying, “Ba-bump. Ba-bump.”

Seeing Hudson run around the exam room, showing off her new words and playful spirit, after a long journey with kidney disease, dialysis and surgery, is deeply rewarding for her medical team.

“That’s why this work is so much fun, because you end up helping these kids and their families,” Dr. Goebel said.

Hudson’s parents just love watching their daughter embrace life—in all her cute toddler ways.

“She is such a silly, silly girl when she is in her own environment. So carefree and just constantly babbling,” Kendra said. “It is so nice having her home.”

“You always want your children to do better than you,” Cody said. “I think she is going to do amazing things with this little piece of help.”

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

Such an amazingly beautiful story of true love

What a selfless gift of love given to her from her Dad! Such loving parents! We are so blessed to have HDCH so close to home to coordinate this surgery and treatments. And to diagnose such a rare disease! Impressive recovery thanks to the whole team!

What a Beautiful story!!

Awesome job dad !!❤️

Praise be to God from whom all blessings flow, There was a huge prayer team praying for this family! Thank you, Jesus!