Nervousness. Reluctance. Doubt.

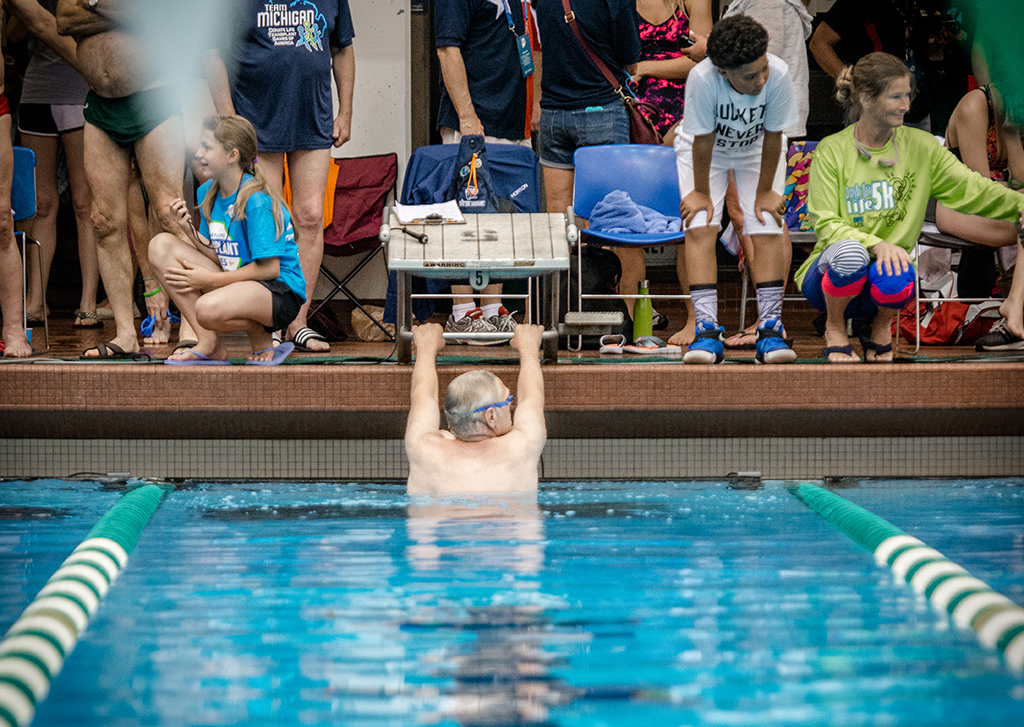

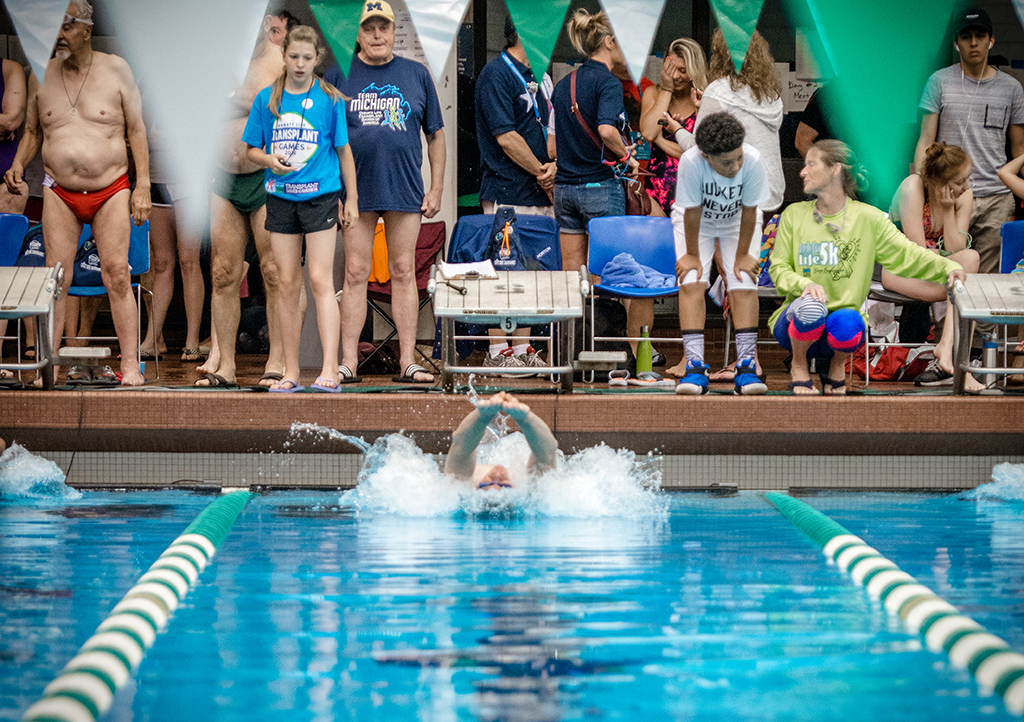

Late Sunday morning, had you been watching closely, you might have caught the moment the lean guy in Lane 5 shrugged off all the deadweight feelings.

They’re probably still down there now, sitting at the bottom of that pool on East 24th Street in Cleveland, slowly disintegrating under 12 crushing feet of electric-blue, Olympics-quality pool water.

Metaphorically, of course. There’s not really anything sitting at the bottom of Cleveland State University’s swimming pool.

Fred Nelis just appreciates a well-placed metaphor.

He readily agrees that he cast off uncertainties someplace along Lane 5, right about the moment it became clear he would dominate his first swim race in the Transplant Games of America.

In the 50-yard backstroke, in his age division, he earned first place. You could have stuffed two dolphins between him and the nearest competitor.

“What was racing through my mind all the time was how bad this is going to hurt,” he said later. “The thing I hate to do is (get) up on the block and wait for the (buzzer) to go off. You’re kind of between here and there. It’s a gray area. It’s mental.”

It’s that moment of anticipation any competitor knows, when the stomach somersaults and the limbs go rubbery.

Nelis also had the added distraction of knowing that, in a few days, he’d celebrate the second anniversary of his heart transplant.

Should this Holland, Michigan, man really be competing—age 61, two years post-transplant—in a punishing sport he and his wife have loved since childhood?

He felt reluctant, nervous.

For a moment.

“It was pretty much gone after that 50-yard backstroke,” he said. “That would have been my weakest race—but I set a tone for the other races.”

About that tone.

The 50-yard backstroke, first place. The 100-yard freestyle, first place. The 50-yard butterfly, first place. The 50-yard freestyle, first place.

Has a nice rhythm to it, right? Like a good, solid heartbeat.

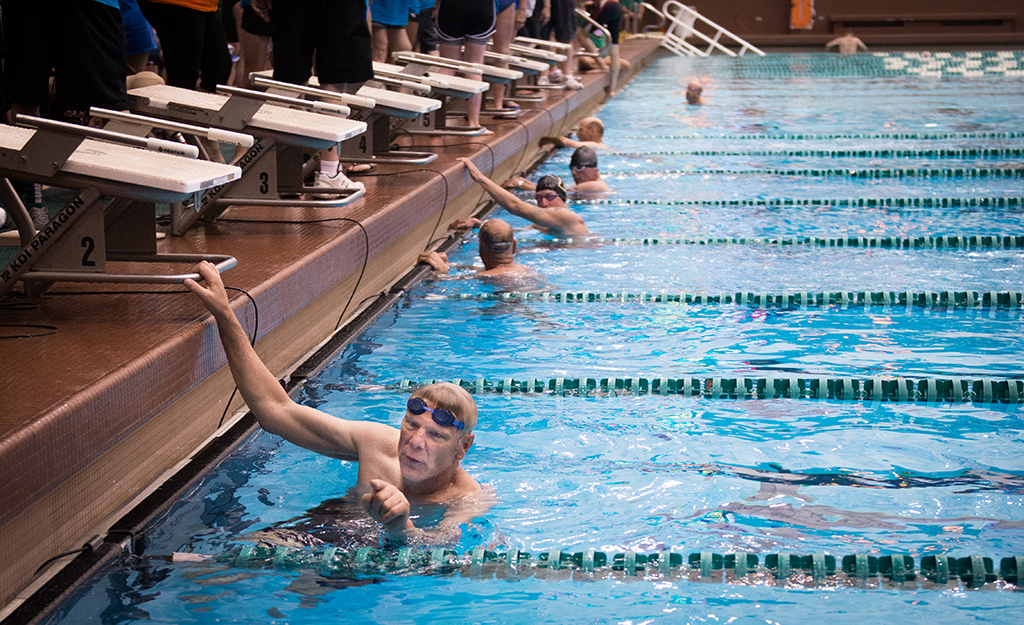

“It’s also a statement,” Nelis said. “That just because we’re transplant recipients, it doesn’t mean we’re porcelain dolls.”

Setting goals

As Nelis finished up his first race Sunday morning, his wife, Jean, 56, had just finished reading an online Spectrum Health Beat story about her husband’s experiences.

It’s been more than 20 years since Nelis learned he had idiopathic cardiomyopathy, a failing heart. He continued to swim competitively in the years that followed, up until about 2011, when his ailment forced him to stop.

In 2013 doctors installed in him a left ventricular assist device, a machine that helped keep him alive but also precluded him from submerging his body in water.

“He’s always been a swimmer,” Jean said. “When he had the LVAD and he couldn’t get wet … he felt so bad. He always wanted to get back in the pool. And a transplant was the way to do that.”

In June 2014, Spectrum Health doctors replaced Nelis’ heart with the heart of a 32-year-old man.

Almost immediately Nelis put the Transplant Games on his radar.

“It was just a goal that I set a few years ago,” he said. “It was something I could focus on to give me direction and purpose. It was going to be a benchmark, a springboard to see where I can go from here.”

It would prove to be a place for camaraderie as much as competition.

Nelis swam in a pair of relay races Sunday with team members from Michigan, who are also organ recipients. Their team won second and third places.

One of those teammates, Holly Werlein, 31, of Grand Rapids, is a patient services representative associate at the Spectrum Health Heart and Lung Specialized Care Clinic.

She and Nelis have crossed paths at her workplace over the years, when he’d appear for appointments. But this was the first time they swam together.

Werlein celebrated the 10th anniversary of her liver transplant the day after the swim competition. She has competed in the Transplant Games, which features organ donors and organ recipients in multiple sports, since 2008.

She remembers how it had been, at first, receiving an organ transplant at age 21.

“I knew nobody who had a transplant,” she said. “When I found the Games, it was like, ‘I’m normal in this environment. I’m happy to be alive.’”

Standing out

It’s not the competitors’ scars or their palmfuls of medication that make them standout.

It’s their aura. Their positivity. Their sense of gratitude and redemption.

“It’s such a positive vibe here,” Werlein said.

Jean noticed it, too, as the wife of a transplant recipient.

“It’s nice to be with people who are in similar circumstances,” Jean said. “Everyone has a story about their transplant. You know you’re with a lucky group, where everyone knows how fortunate they are.”

Saturday night, in the opening ceremonies of the Transplant Games, organizers featured the families of the organ donors prominently.

“It was so emotional,” Jean said. “The athletes all come in by their states, and then the donor families come in. And they get more applause than the athletes.”

In the swim competition, many of the competitors write the donors’ names on their backs. Some write the name of the organ they received, or donated, alongside the year of the surgery.

When Nelis looked around at the other competitors, he saw men and women, boys and girls, young and old, all shapes and sizes. Many had great physiques. Many bore scars on their abdomens, chests, backs and torsos.

And almost to the person, they had terrific smiles on their faces.

“I feel the same as everyone else does here,” Nelis said. “Very grateful to be alive. In my case, though, the donor had died. He was only 32.”

In an interview with a TV station in Michigan just before the Transplant Games, Nelis equated the journey of the transplant patient-turned-competitor to that of the phoenix.

“The mythical bird,” Nelis said. “Rising from the ashes and flying again. You’re never the same again.”

That’s the Transplant Games, he said.

“This is the chance when all the birds of a feather fly together,” he said. “All these phoenixes here celebrating.”

Not a day goes by that he doesn’t pause, at least once, to feel grateful.

“Every day that I get up—brushing my teeth, washing my face, standing at the mirror—I look at the scars that are on my chest,” Nelis said. “And I know they’re there because someone else gave me another chance. Someone who didn’t know me.

“I just sit there and get chills thinking about it,” he said. “It happens every single day. The newness, the freshness, it hasn’t worn off. It’s there every time I look at my chest. There’s somebody else inside of me.”

If the Transplant Games are emblematic of second chances and lives well-lived, Nelis is living large.

And he’s just getting started.

One of the swimmers at Sunday’s competition approached him after noticing his impressive debut.

“You know,” the guy told Nelis, “we’re going to go to the World Games next year, and we’d really like to beat the Brits and the Aussies. I really think we could do it if you swim for us.”

His new goal has emerged: the 21st World Transplant Games in Spain, summer 2017.

“The other folks on the team, they want to press me into service in Spain,” Nelis said, chuckling. “That would be fun. I told them I’ll swim as fast as I can.”

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>