In the late 1940s, fresh off World War II, the United States found itself confronting a deadlier enemy yet.

Heart disease.

In that post-war universe, where advancements in medical knowledge had finally reined in infectious disease fatalities, cardiovascular disease emerged as the leading threat, laying claim to half of all adult deaths in the U.S. each year.

In 1945, a year after the war’s end, hypertensive heart disease and stroke killed President Franklin Roosevelt. Three years later, successor Harry Truman recognized the urgency of the threat and signed off on the National Heart Act, allocating $500,000 to fund a 20-year study of heart disease.

That deep-dive became the Framingham Heart Study. It marshaled 5,200 men and women to undergo periodic examinations, with cardiovascular conditions top of mind.

The study hit the 20-year mark, but then persisted. It went long beyond the expiration date, in fact, gradually enlisting children and grandchildren of the original cohorts. Seven decades later, Framingham continues reeling in data.

The study has served an outsized role in strengthening modern medicine’s comprehension of cardiovascular conditions, said Dave Chesla, PA, director of research operations at the Spectrum Health Universal Biorepository.

“It’s not very big, not very diverse, but it’s so valuable because those individuals stayed engaged throughout their lifetime,” Chesla said. “We know everything we know about cardiovascular disease largely as a result of that small group.”

Why this little snapshot of history? Handy perspective.

Framingham began somewhat humbly, but morphed into a 70-year-and-counting, multimillion-dollar study. It has built up a vast depot of important medical knowledge.

Now, in this innovative age of all things technological, the United States seeks to grow the concept exponentially.

Instead of 5,200 participants, make it 1 million.

Instead of $500,000, make it $1.5 billion.

And start with a decade of study. Don’t limit the focus to heart disease, either. Focus on overall health—good health, poor health, all matters in between. Survey all races, genders and socioeconomic backgrounds.

Finally, package up all that volunteered data—blood biospecimens, genomic information, personal health surveys—and use mankind’s latest, greatest tech gadgetry to sift and winnow it for insights into health and wellness conditions in all corners of the country.

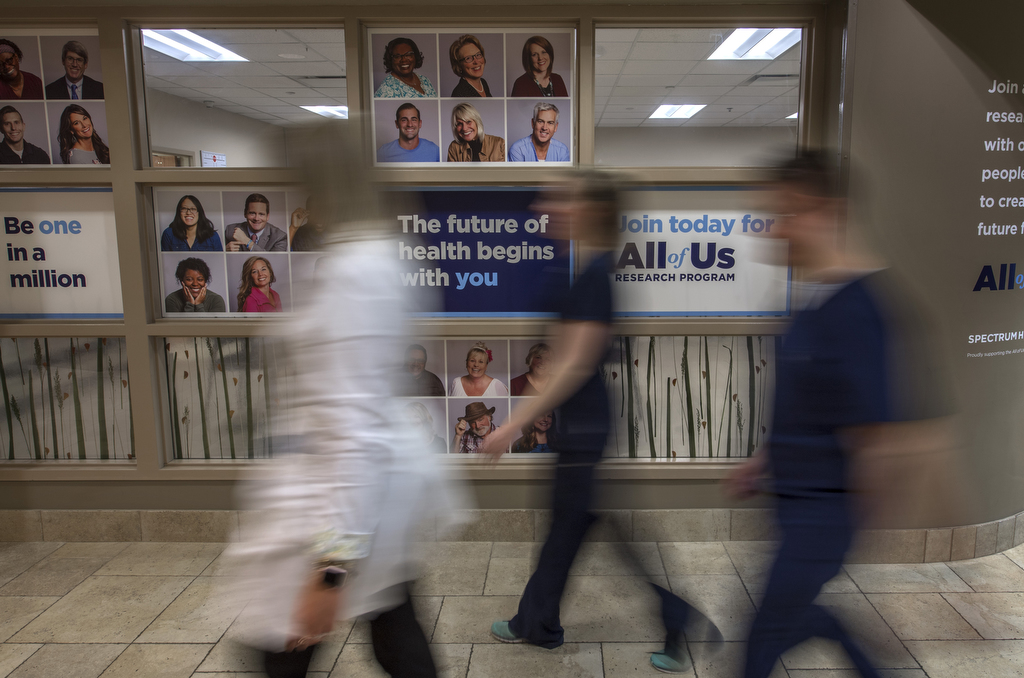

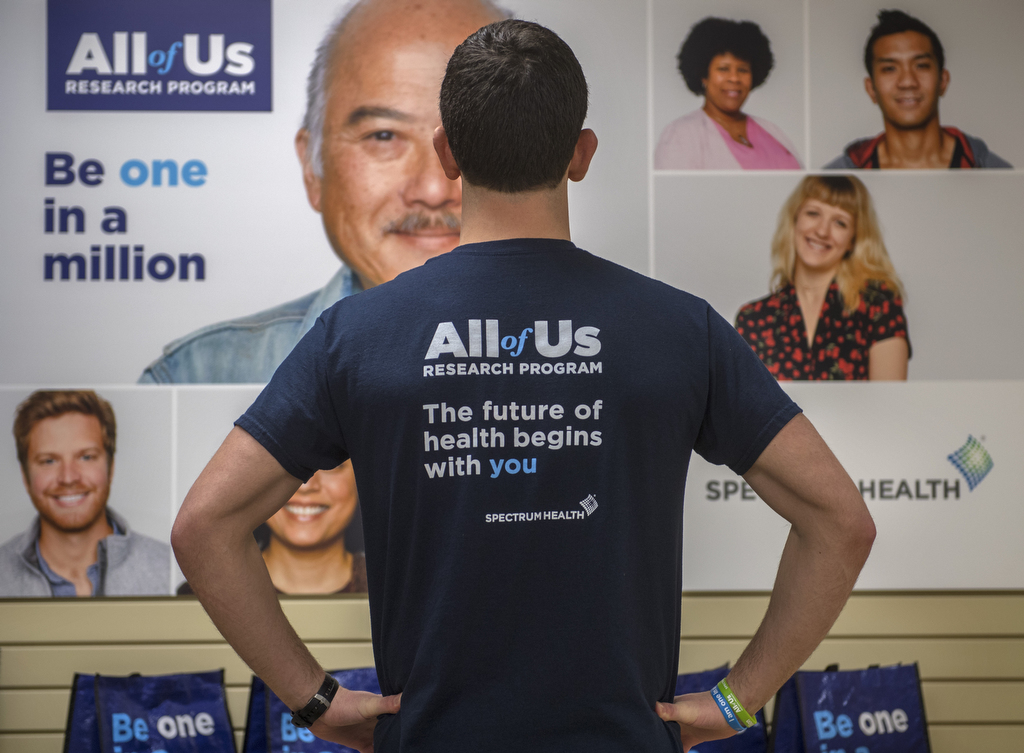

Dub it All of Us.

If it works as intended, it might become to Framingham what Amazon.com is to the corner grocer.

A shared story

The All of Us Research Program is a National Institutes of Health project that aims to accelerate medical research to achieve better health for people of all backgrounds.

The program’s website sums it smartly: A “participant-engaged, data-driven enterprise supporting research at the intersection of human biology, behavior, genetics, environment, data science, computation and much more to produce new knowledge with the goal of developing more effective ways to treat disease.”

Sounds wonderfully simple in a sentence. Logistically, it’s a colossus.

Unlike most research studies, which focus on a specific disease or a specific population, the All of Us Research Program is not constrained by health conditions or personal characteristics, Chesla said.

It is sharply focused on accumulating health data and genomics info on individuals from all walks of life, then crunching the data to deeply understand what might lead to good health or poor health.

That’s the “All” part.

Of course, no matter how wonderful your electronic wizardry, you still need a compelling “people” story if you want to attract interest.

Hence the “Us” part.

“What makes it unique is the participants and our partners,” Chesla said. “Oftentimes, research is focused on disease orientation. Either you have research studies that target a specific cancer, or a very specific cardiovascular element.”

In those targeted studies, researchers aim to deliver new devices or new treatments. In All of Us, Chesla said, the researchers will aim to share the data with other researchers—and with the participants themselves.

It’s an uncommon level of transparency, Chesla said.

“Not only can you participate, but there’s a bidirectional flow of information that really differentiates this program,” he said. “As a participant, I can go online through my participant portal, see my information and also glean new information about myself.”

As scope and scale goes, the project is indeed unrivaled.

“To do a large population study of this nature, where anyone is eligible that lives in the United States, and it’s agnostic to a state of disease or wellness, is unique,” Chesla said.

West Michigan is currently one of the pilot markets, served by Spectrum Health. Enrollment is open to current and prior Spectrum Health patients ages 18 and older living in the U.S.

Enrollment will eventually open to everyone in late spring.

Those interested can sign up at one of seven locations, or start the journey at the Spectrum Health All of Us page by clicking “Join Today.” From there you’ll complete a short survey and then choose a preferred enrollment location where you provide blood and urine samples.

‘Badge of honor’

Steve Heacock, senior vice president of marketing and public affairs at Spectrum Health, has the distinction of being the first Spectrum Health employee to sign up for All of Us. A Spectrum Health employee drew his blood at a test location and he filled out his survey.

“That’s all I’ve done so far,” he said. “We’re in such an early stage.”

Heacock is eager for big things from this program, and not necessarily for himself.

“This really is about contributing to this huge effort, this huge move forward in science and research,” he said, painting his participation as a “badge of honor.”

“Contributing to that body of science that’s going to help push innovation forward is a positive thing,” he elaborated.

As Heacock sees it, we are each a piece of something much bigger than ourselves. Participation in All of Us would be a small but significant contribution toward that greater purpose.

“You realize, ‘I’m part of a continuing stream,'” Heacock said. “It’s one life, and one life is important and significant, but it sort of gets fuzzed up in the whole.”

Think of it: We remember our grandparents, and maybe our great grandparents—but what about their parents? And theirs? Beyond that, the history gets dicey.

“So, generation after generation, we just kind of keep moving ahead,” Heacock said. “But it doesn’t mean it’s gone. It’s a continuing stream. This DNA stuff proves that out, when you can reach back to ancient times. It’s kind of exciting.”

The All of Us Research Program is “the carrying forward of that stream,” he said.

Even so, if researchers hope to meet their 1 million-person goal, enrollment—and continuing involvement—will need to be swift and simple.

Based on initial accounts, the project architects have designed it just so.

“I don’t view it as a burden going forward at all,” Heacock said. “I’ll do it the rest of my life. It’s an annual survey that’s easy to do if you pay attention to your medical stuff.”

From a time standpoint, commitment is minimal, he said.

“It’s very, very little,” Heacock said. “It’s about allowing access to my information. It is allowing them to access my medical records, because they need the full picture.”

Best of all, Chesla said, each participant can handcraft their own path.

“Your level of engagement could be, on day one, ‘I did the bio-specimens, I did the surveys online, and now I just don’t have an interest because I have small children or I became ill or that’s the level of participation I want to commit,'” Chesla said.

You could then opt out.

“That doesn’t mean you don’t get to see your test results,” Chesla said. “It just means you’re no longer going to provide anything.”

Or you could march on, full-tilt.

“You could be the ultimate participant who buys in for 10 years and repeats their surveys every year, because that would provide statistical measures for scientists,” Chesla said. “And also get selected for a breakout study.”

One of the breakout studies involves Fitbit providing wearable devices to 10,000 participants.

“Anyone in that 10,000 would have to come back in and get fitted for the device, then learn how to use the device to make sure they have additional needs in the home—WiFi or laptop to upload the data,” Chesla said.

A participant’s level of engagement determines not only the value to science, but the value proposition back to the individual.

“They get more data back the more they participate,” Chesla said. “It’s not meant to be a hook, if you will. At the end of the day, it’s just how research works—the more we know about an individual in the population, the more we can interrogate the data to look for common themes or threads of illness or disease or cofactors.”

The All of Us campaign has even created a web page where participants can suggest novel research ideas for the data.

‘Fine-grained’

Medical research studies typically survey a few hundred or a few thousand people—not tens of thousands or, in this case, 1 million.

The salience of All of Us is its wide-scale data collection and analysis. A statistical study of this magnitude would allow researchers to make “fine-grained” predictions about how a certain treatment may affect a certain individual.

To achieve this, it targets key populations, no matter how grandiose or granular the end game. A “nondiscriminatory approach” that pulls in a diversity of participants will provide the most robust sampling, Chesla said.

“The NIH has been very specific on the application,” he said. “The All of Us program will over-represent populations that are traditionally underrepresented in biomedical research.”

It is perhaps unsurprising that the original participants of the Framingham study were primarily white.

“Eighty percent of them were Caucasian males,” Chesla said.

Rural, urban, poor and minority populations have historically been under-represented in scientific research, Chesla said.

The last thing the NIH wants is to cater to over-sampled majorities.

Heacock hammered on this point.

“Think of the experience of communities of color, with how they were treated and where they are, and the mistrust that must be overcome,” Heacock said. “The only way this science is going to be applicable overall is if everybody participates. If we do this right, we’ll be in great shape.”

Said Chesla: “We lack diversity and socioeconomics because individuals who don’t have insurance don’t get into clinical trials and often Medicaid doesn’t cover that.”

And then there’s the age element.

Given medicine’s often reactive nature, there’s not as much medical data on populations younger than age 65.

The All of Us program stems from the Precision Medicine Initiative, an Obama administration idea to proactively promote health care personalized to individual characteristics and needs.

This means All of Us, by definition, seeks to be more proactive and all-inclusive.

“Everyone is equal in this program,” Chesla said. “An 18-year-old who is healthy and is technologically savvy and has buy-in to stay in the program for 10 years is every bit as advantageous to research as an 89-year-old who is a model of health and has lived 12 years longer than the average male or female in the Unites States.”

Likewise, an 89-year old battling a host of ailments is equally welcome.

“Why do some people succumb to an illness and why do some people move past it?” Chesla said. “Those are questions we can’t answer right now.

“We can look at it side by side, but at a population level we can’t tease out the predictors about how someone will respond or how we engage them when they’re well, and maintain that wellness with them so that we’re truly about ‘health care’ and not about ‘disease care.'”

In respect to size, scope, ambition and capabilities, the All of Us study is unprecedented in its aim to reveal these hidden predictors.

“Spread that out to 1 million people, being intentional about geography, diversity or however you want to measure it—and then add all of the modern-day technology—and you have something very unique and special,” Chesla said. “This is a $1.5 billion program over 10 years, with 1 million individuals.”

Those with a medical or epidemiology background say this is a modern-day Framingham study.

Seventy years from now—though likely much sooner—your children, grandchildren or great-grandchildren may reap the benefits.

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>