Derek Dool began having seizures at age 6.

In the worst of times, he could have up to 150 seizures in a single night.

Doctors diagnosed him with epilepsy as a child. He had to give up much, including his sports dreams.

“They stopped me from playing football,” Derek said.

He’s now 32 years old—and he’s given up plenty more over the years because of the seizures.

“I can’t drive because I need to be seizure-free for six months,” Derek said.

Still, he isn’t one to feel sorry for himself. When someone expresses concern or sympathy for his difficulties, he often responds with a quirky, “You can stuff your sorries in a sack.”

New vistas

Medications have helped Derek manage the epileptic seizures to some extent, but the effectiveness diminishes over time.

Doctors tried responsive neurostimulation, or RNS, an implanted device that monitors brain activity and detects the start of a seizure, then delivers a response to curtail it.

That helped, too, but the device can only target one area of the brain.

Hoping to turn things around for Derek, Sanjay Patra, MD, division chief of neurosurgery at Spectrum Health, selected him to receive the newest technology in deep brain stimulation.

In early June, Derek became the first person in the country to receive the Medtronic SenSight Directional Lead System to control his epileptic seizures.

The Food and Drug Administration approved the device in May.

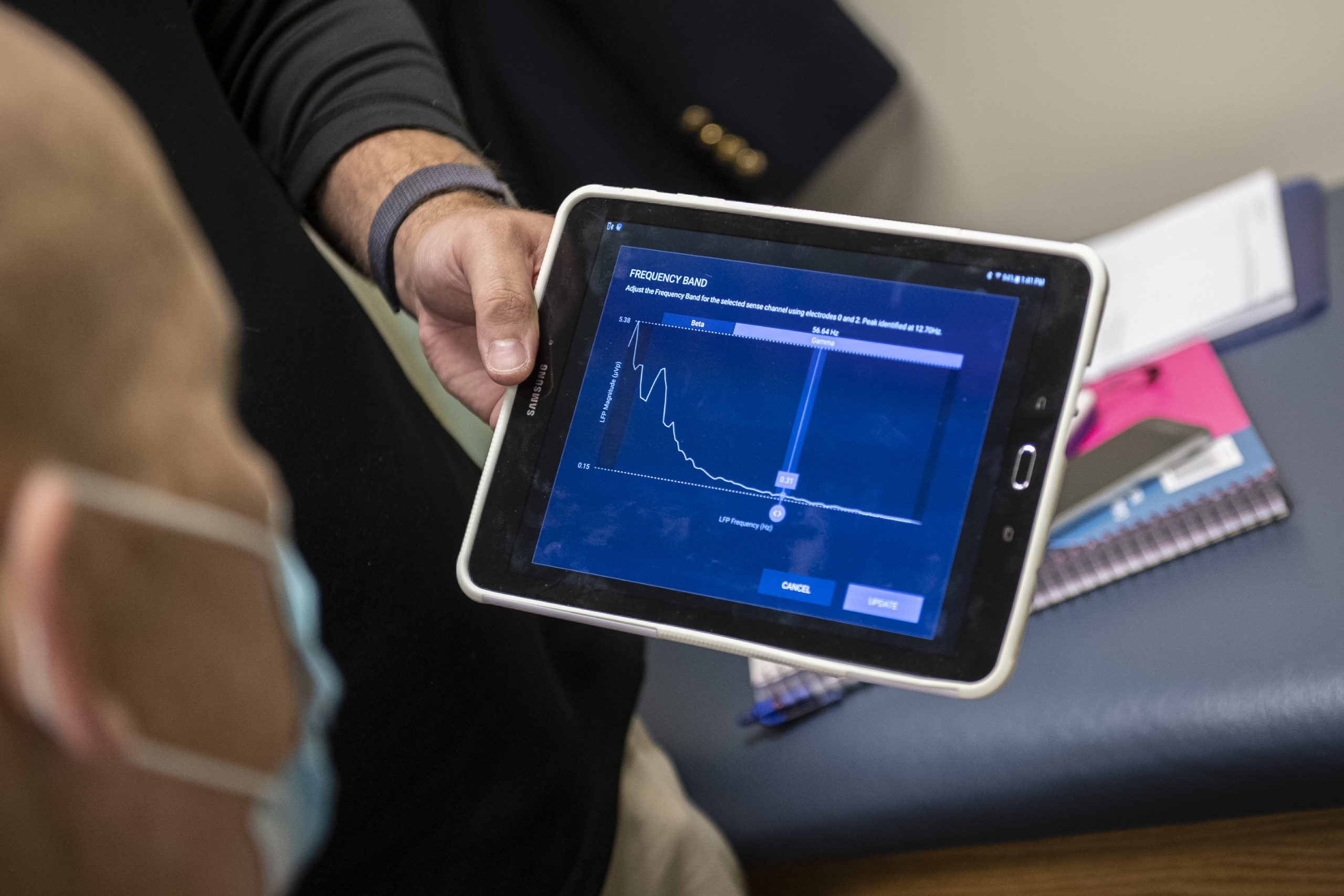

It’s different from the traditional deep brain stimulating system in that it can be programmed to deliver more precise and targeted electronic signals to disrupt a seizure.

Also, doctors can detect patterns and adjust both the intensity and precise location of the response delivered by the new device.

“This is more personalized medicine,” Dr. Patra said. “The main advancement here is that the surgeon and the epileptologist can look at a patient’s individual brain signature and optimize the settings to deliver the correct stimulation.”

Over time, doctors hope to significantly reduce the frequency and severity of Derek’s seizures.

They also hope the device will assist in retraining the neurons in Derek’s brain, making them react in a way that won’t produce as many seizures, said David Burdette, MD, section chief of epilepsy at Spectrum Health.

“We aren’t quite sure how that works,” Dr. Patra said of the brain’s response. “But we are hoping for a 70 to 80% reduction in seizures after two or three years.”

This opens up significant vistas in the field of epileptology, Dr. Burdette said.

Feeling hopeful

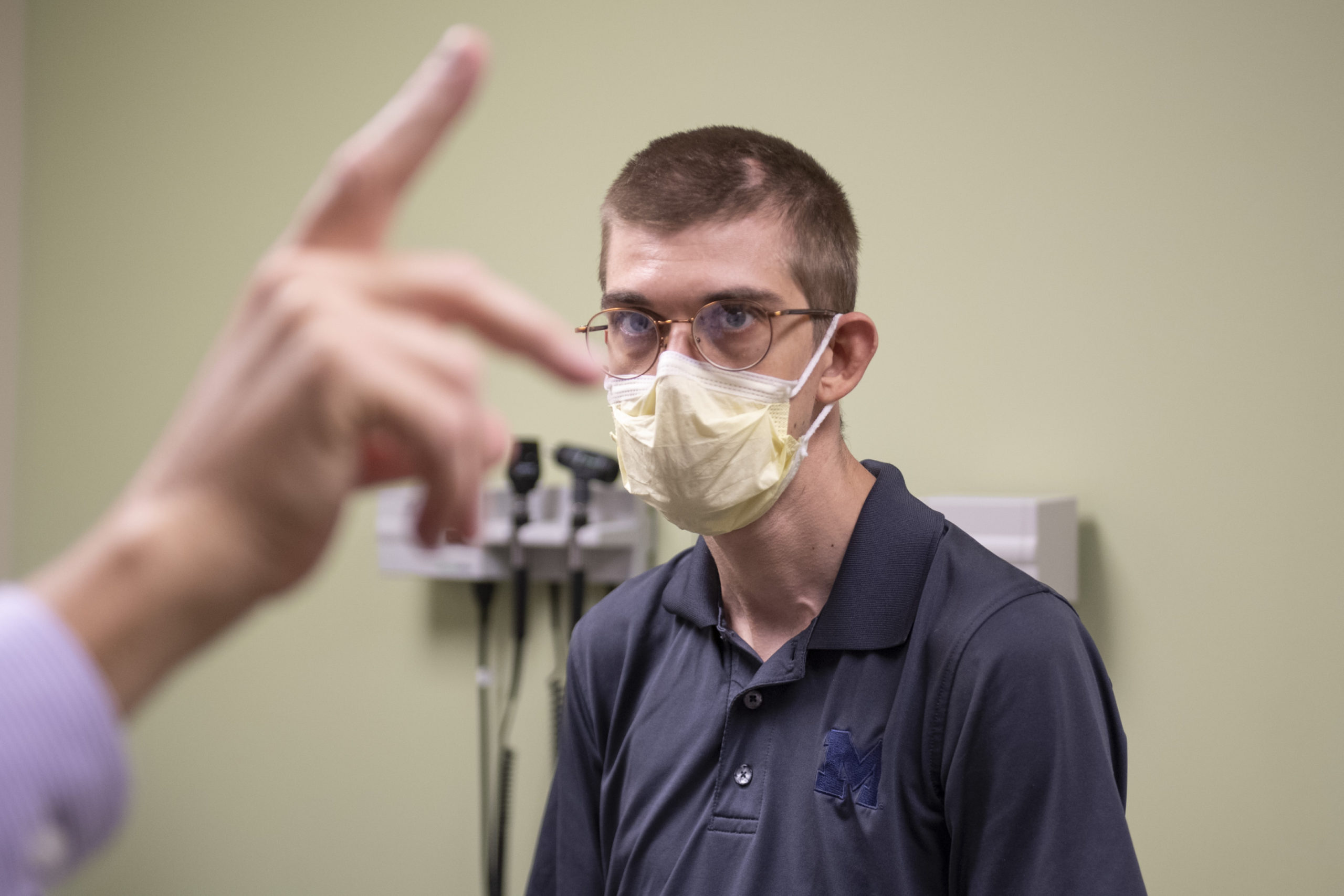

During a recent check-up—about three months after the deep brain stimulation device had been implanted in Derek—Dr. Burdette tweaked the settings while Derek sat quietly and waited to see how his body would respond.

In his quiet and halting voice, Derek indicated when he felt tingles in his limbs or heat on his face.

The two leads that doctors surgically implanted in Derek’s head have three segments that can direct four different levels of electronic impulses to fire in certain directions.

Derek lives with his mother and legal guardian, Tracey Dool, in Cassopolis, Michigan.

She’s the keeper of what’s called the “patient communicator”—a white, pocket-sized gadget that allows her to manually activate the deep brain stimulation system.

It’s programmed to automatically deliver one minute of electrical impulse every six minutes.

If Derek begins to have a seizure, his mom can turn it on manually so it will disrupt the seizure and also record the brain’s activity.

This information, which can be downloaded during an office visit, helps Dr. Burdette determine the exact location and severity of each seizure.

“When I hit the device I can see it calm him,” Tracey said. “The seizures aren’t as strong or violent.”

Both she and Derek admit to sometimes losing hope that he could lead a semblance of a normal life—free of seizures, free of side effects from epilepsy medications, cleared to drive, able to hold down a job.

But these days, they’re feeling more hopeful.

“We have lowered his medications, but as time goes on I’m hoping he can get off all of them,” Tracey said. “With this new device I can see a difference. This is what keeps us going now.

“This gives us power over the seizures. That’s what everyone should have.”

Restorative therapy

Already, things are looking up for Derek.

He picked up the guitar he hadn’t played in many months. He’s been doing a little exercise now and again and is getting up earlier each morning.

He’s still having seizures, about four or so a week, Tracey said, but he’s on smaller doses of some medications “and he seems more alert, quicker to answer when I ask him a question, which is really good.”

The doctors are optimistic, too.

Historically, severe cases of epilepsy were treated with destructive therapies, such as using a laser to eradicate small sections of the brain where seizures occurred, Dr. Patra said.

The newer restorative therapies are promising “because, obviously, an intact brain is better than a non-intact brain,” Dr. Patra said.

“Derek’s progress will help others, too,” Dr. Burdette said.

Derek’s case is the most difficult one he has encountered in his 30 years of work in the field of epilepsy, Dr. Burdette said.

But new discoveries are boosting hope.

“It’s exciting to be an epilepsy surgeon right now simply because there are so many treatments around,” Dr. Patra said. “We are making a lot of progress for patients like Derek, whose epilepsy cannot be controlled by medications alone. Even five years ago, there were not a lot of options.”

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>